Designed by two of the world’s greatest architects – Fumihiko Maki of Japan and Charles Correa of Mumbai – the twin masterpieces are a spiritual, educational and architectural destination in Toronto’s north end.

Despite its boxy profile and ultra-white Brazilian granite cladding, which project a sense of hefty permanence, the Aga Khan Museum is all about light. You notice this as soon as you arrive at the 6.8-hectare complex in the north end of Toronto. The canted walls catch and reflect the sun, casting hard-edged shadows with graphic clarity. Designed by Japanese architect and Pritzker Prize winner Fumihiko Maki, the 11,500-square-metre building is one of three remarkable creations completed on the site last year. Joining it is the Ismaili Centre, by Mumbai architect Charles Correa, along with a garden of reflective pools by Lebanese-Serbian landscape architect Vladimir Djurovic.

Light, though, is not strictly used for optical effect. It also creates a visual metaphor that radiates throughout all three projects. In the museum, 12-metre-high curtain walls make up a central atrium, etched in an Islamic-inspired mashrabiya pattern. During the day, the geometry draws intricate, roving shadows across the white walls and heated limestone floors; in the upper galleries, meanwhile, hexagonal skylights allow glimpses of blue sky. Commissioned by His Highness the Aga Khan, the spiritual leader of the world’s disparate Shia Ismaili Muslim population, the museum is intended as a place for all faiths and an institution that brings Islamic culture to the western world.

A 20-minute drive from downtown Toronto, surrounded by nondescript office parks and mid-rise condos, the site is actually at the centre of one of North America’s most diverse and densely populated regions, with over eight million residents within a 160-kilometre radius. Moreover, it is highly visible. Alongside the Don Valley Parkway, the museum’s flat roof and the Ismaili Centre’s faceted glass dome can be seen beyond a grassy rise, like beacons to the tens of thousands of people who drive by each day.

The grounds could easily feel overwhelming, but Djurovic’s gardens expertly balance proportions. Five black granite reflecting pools, which rise to about knee height, have wafer-thin cascades of water flowing along their perimeters. It was a major challenge to make each pool perfectly level, to maintain an even flow; settlement, harsh frosts and thaw cycles were the main concerns. “We poured the structures at a very early stage,” says Djurovic, “to allow them to settle for over a year before finishing the details.” Interspersed between the pools are groves of allegheny serviceberry trees, and clipped hedges surround the formal garden. The whooshing traffic noise of the nearby highway is replaced by the more meditative sound of gravel crunching underfoot.

Not every guest will visit the manicured grounds for a first experience – many will drive directly into the underground garage – but the introduction will be just as transcendent. The garage is linked to a long ramped hallway, with a ceiling painted navy blue and flecked with gold. It ends at a small room wrapped in black granite, which feels dark and compressive. Visitors ascend a flight of stairs before stepping into the museum’s main atrium, where the eye is drawn up and out to the sky.

The whole thing could seem overwhelming, if not for Maki’s masterful countering of monumental and human scale. Tall columns line up with one-metre-square pavers that meet wall panels a metre wide. “The precise alignments create a sense of comfort,” explains project architect C. Po Ma, of Toronto’s Moriyama & Teshima, the architects of record for all three projects. “Even if the mind doesn’t perceive it consciously or understand why, the eye picks up on it.”

The atrium is the central circulation organizer, directing visitors. At one end, a granite staircase leads to the temporary exhibition hall, while the permanent collection – the Aga Khan’s personal holdings of more than 1,000 objects from over 10 centuries – opens up through a set of doors on the main level. At another end, doors inset within oyster-coloured panels lead to a 350-seat auditorium lined in teak, with seats upholstered in bright blue (the Aga Khan’s favourite colour). The atrium is also aligned with the main hall, which, through large windows, perfectly frames the gardens and the Ismaili Centre beyond. In composing the museum, Maki considered the centre as the most prized artifact, because of its spiritual significance. (The Aga Khan Museum is a finalist of the 2015 AZ Awards.)

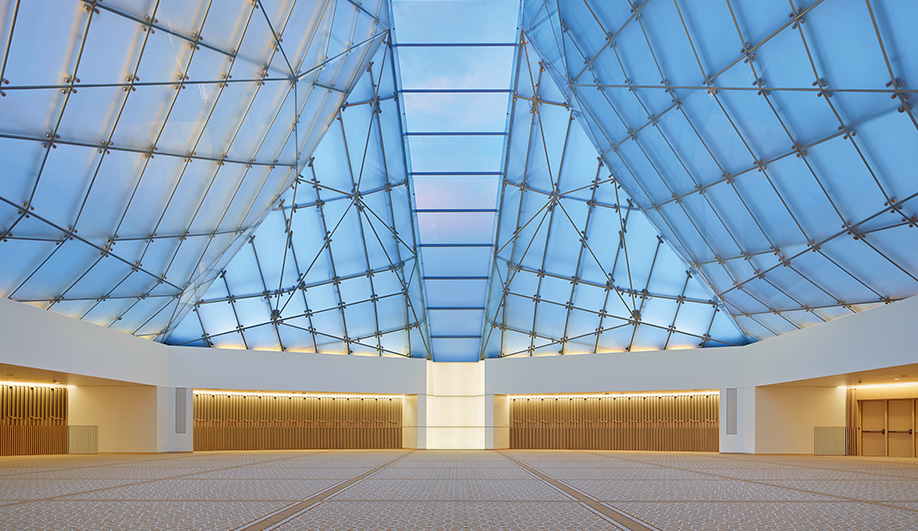

While the Ismaili Centre is less accessible to the public than the museum (during prayer times, the hall is reserved for followers of the faith), it was still designed with light and openness at its core. The front doors are set within a sweeping limestone wall, and the plan of the prayer hall is a circle. For Correa, both are architectural metaphors of welcoming, all-embracing arms. Arriz Hassam, of Toronto’s Arriz+Co, and British firm Gotham Notting Hill collaborated on the interior finishes, which also express a sense of openness. The main lobby, meeting hall and offices are separated by transparent walls etched with a motif of Hassam’s own design, based on a fractal pattern inspired by the geometries of Correa’s prayer hall dome. The pattern is repeated on the stone floors, carpeting and screens; the composition of stars and circles alludes to both celestial divinity and earthly inclusivity.

The symbolism peaks in the prayer hall: the circular anteroom at the entrance is crowned by a modern take on a muqarnas ceiling, with a conical skylight at its apex, and the walls are lined in wooden screens inscribed with the word “Allah.” Says Hassam, who arrived in the 1970s as a refugee from Uganda, “I wanted to make the space to reflect the spirit of Canada’s pluralistic society.”

The muted tones and subtle patterns give way to the soaring glass dome, the centre’s most awe-inspiring feature, crafted from sealed panes of double-sided frosted glass to improve thermal performance. The central spine – the one that faces Mecca – towers out of a sculptural installation made of onyx, offering clear views of the sky. Regardless of one’s faith, the dome is a stirring sight, with its glorious, uninterrupted blaze of light.