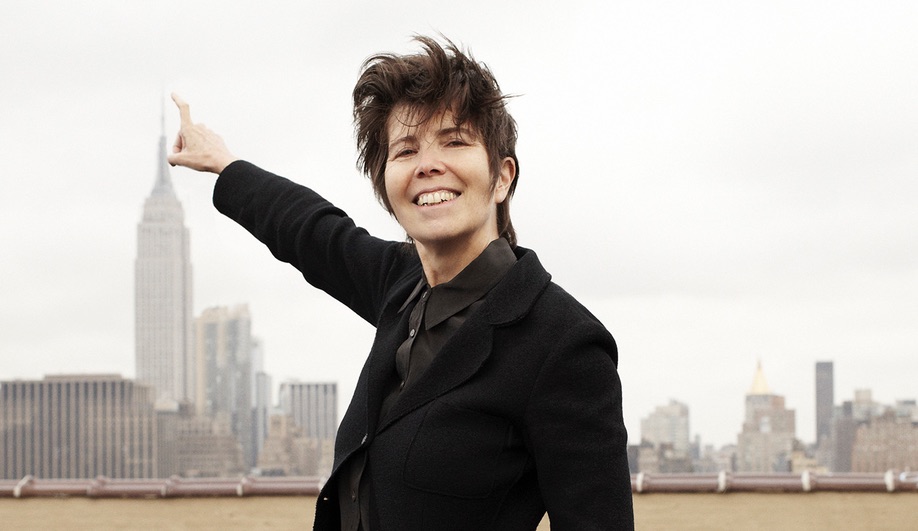

As a principal of Diller Scofidio + Renfro, the interdisciplinary New York studio she co-founded with Ricardo Scofidio in 1981, Liz Diller has realized her progressive ideas about space making through many of her home city’s most iconic projects, from the High Line and the revamping of Lincoln Center’s public areas to one of next year’s most anticipated unveilings: the Shed, a 19,000-square-metre art and performance structure created in collaboration with the Rockwell Group.

The mammoth new building, on Manhattan’s west side, boasts a telescoping outer shell that doubles its footprint as needed. Recently, Diller sat down to discuss the challenges of working on landmark projects in an ever-changing metropolis, offering a few key lessons in the process.

1 Take full advantage of enlightened municipal leaders.

Under Mayor Giuliani there was no urban thinking; it was fairly repressive, and the High Line was about to be demolished. When Michael Bloomberg took over, things really changed. Bloomberg employed interesting people as cultural and planning commissioners, and he was very open to new ideas, and new initiatives such as the High Line. He was often accused of giving everything away to developers, but he had a real interest in the culture around him as well as an entrepreneurial streak.

2 Be flexible, as city hall cultures change.

Bill de Blasio, the current mayor, has his own social agenda, but he doesn’t really understand the role of architecture and public space. [Last September] was the first time he had ever set foot on the High Line. That’s mind-blowing!

3 Never doubt the healing power of architecture.

What emerged after 9/11 was fear and vulnerability, but also a sense of civic pride. And some of our biggest projects – such as the High Line – reflected that. When they opened, they were received almost like gifts. No one was expecting them, so the public just embraced them with great sentiment. If 9/11 hadn’t happened, I doubt that these projects would have happened.

4 Gentrification isn’t always a bad thing.

Gentrification is part of New York City, part of our DNA. And a lot of people don’t understand its full meaning from an urbanistic standpoint, its positive aspects. But it does need to be controlled. The Shed, frankly, is an attempt to reassert New York City’s position as a place for artists, to push ways for artists to work together, in public, in a different kind of format. It’s not about making another museum.

5 Think big picture and (very) long term.

What will culture look like in 10 or 20 years’ time? We have no idea! The best thing that we as architects can do is make an infrastructure for art. The Shed will challenge curators, artists and the public with new possibilities. And since space is the most valuable commodity we have, it will preserve a part of the city for culture in the future.

This story was taken from the March/April 2018 issue of Azure. Buy a copy of the issue here, or subscribe here.