If you haven’t seen or read it yet, the October issue of Azure features an in-depth article on gender inequality in architecture. Written by Montreal journalist Linda Besner, the story outlines how a profession that prides itself on innovation has failed to overcome the glass ceiling syndrome when it comes to female architects. The statistics are as stark as the anecdotes. Many women in the profession report pay inequality and that they’ve been routinely overlooked for promotions, while statistical data backs up the fact that gender discrimination remains alive and well. In Canada, Besner writes, only 29 per cent of practicing architects are female. The numbers are even lower in the U.K. (26 per cent) and in the U.S. (24 per cent).

So, what has been lost in this imbalance? What does design lose when female architects and their perspectives are not an integral part of our built reality? We posed this question to 10 leading architects who understand first-hand the particular challenges women face. Here’s what they told us.

“The world loses lateral thinking, which relates to our ability to make creative connections between things that might be assumed to be discrete. We need to think more about how things are—or could be—imagined relationally in the world. This includes the ability to imagine technology, nature and the built environment as integral parts of a singular spatial system, what we have called ‘soft’ design.”

— Sheila Kennedy, Professor of Architecture at MIT, Director of Design & Applied Research at MATx, and principal of Kennedy & Violich Architecture, Ltd.

“Women excel at designing to a human scale and have incredible artistic sensibilities. Their influence secures a holistic approach to architecture, and, in our experience, often refrain from getting lost in technical solutions and details. Architecture must create connectivity between people, and women are important in shaping and developing these designs.”

— Frida Ferdinand & Mette Kynne Frandsen, Henning Larsen Architects, Copenhagen

“Research shows that innovation occurs when there is a nearly equal team of men and women. It’s also been found that companies with more women in executive positions achieve better financial performance. We are designing and problem solving for a very diverse set of people, needs, desires and values—the people at the helm had better be able to approach these challenges with an equally diverse set of ways of seeing the world.”

— Monica Adair, co-founding partner of Acre Architects, St. John, New Brunswick, RAIC 2015 Young Architect Award recipient

“I have been thinking about this question a lot… in the end, in this day and culture I reject the notion that, as a rule, women’s designs can be picked out from a line of buildings. To me they cannot—great architecture is great architecture. Women are equally capable of producing potent and powerful architecture as men are. And I am not able to pinpoint any specific characteristics that I could assign to a female architect alone. What would these more feminine characteristics be? The typical labels such as ‘soft’ and ‘more inviting’?”

— Johanna Hurme, founding principal of 5468796 Architecture, Winnipeg, Canada

– Gabriela Carrillo, principal of Taller de Arquitectura-Mauricio Rocha + Gabriela Carrillo, Mexico City, and 2017

“I will answer your question with a statement by my husband Massimiliano Fuksas: “Doriana sees, and sees with an incredible speed if something works or not. The feminine qualities are: an unimaginable strength, a lot of courage, extensive determination, more than men have”. I totally agree with him because, in my experience, this criteria is applicable when working on small projects because when you work on a small project you see the interior base and form and you can have a global check on material details and the project becomes like a jewel, and so, if there is something that does not work, it is more evident and so you have to check and control every small piece. Therefore, attention to detail, for sure, is typical of women.”

– Doriana Fuksas, principal at Studio Fuksas, Rome, Italy

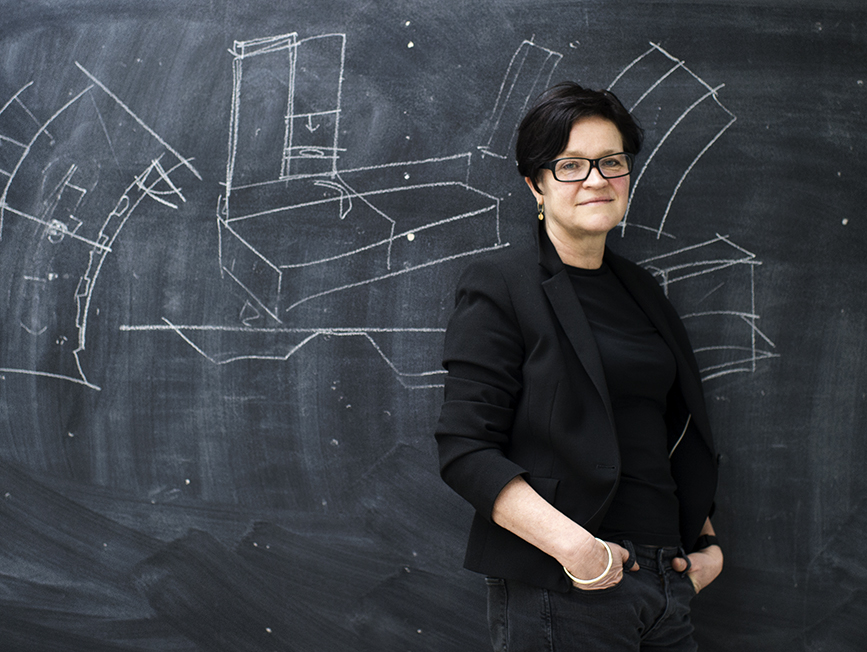

“Each building is designed by the priorities placed onto the project by the client, the jurisdiction, the site and by the architects’ vision and experience. As architects, we are trained to understand and contemplate a variety of often incompatible views—it is our work to find balance in those views. This is a question of philosophy, not gender. The same thing that is lost when any other influences or perspectives are not integrated into our built reality: a segregationist, generalized urban environment that fails to reflect our shared humanity.

— Marianne Amodio, founding principal of MAAStudio, Vancouver, Canada

“Since women make up half of the population, half of what it should be and half of what it could be is lost when women are not an integral part of the process. The narrative, aesthetics and professional structure of architecture have been built up over centuries almost exclusively by men, so for women to be part of the conversation, it takes many of us to write, build and interpret – to make contribution to the discipline as well as the build-environment. We have come a long way in the past 50 years to gain access to the field, but there is still a long way to go.”

– Jing Liu, founding principal of SO-IL, New York

“I don’t think you can generalize about a male or female perspective. But I do think that multiple perspectives, personalities and cultural viewpoints only enrich the design process and the built environment. As a young female architect, it is extremely important to have female influencers we can look up to.”

— Jodi Batay-Csorba, founding principal of Batay-Csorba Architects, Toronto, Canada

– Joan Blumenfeld, principal at Perkins + Will, New York

“Jane Jacobs said it the best: ‘Cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody.’ When female influences and perspectives are not part of the design of our built reality, we lose out on making our workplaces, homes and cities places where women can thrive and be equal citizens.”

— Joy Charbonneau, artist, designer and architect at KPMB, Toronto, Canada

Responses have been edited for length and clarity. This story was taken from the October 2017 issue of Azure. What do you think? Send your feedback to editorial2 [at] azureonline [dot] com.