Canada’s busiest arrival point is undergoing a dramatic rebirth that will see the Beaux Arts station in Toronto transformed into an epicentre for tourism, food and culture.

When Zeidler Partnership senior partner Tarek El-Khatib began thinking about rebuilding the aging train shed at Union Station, one of Toronto’s most iconic buildings, he quickly realized that his team had to confront the facility’s formidable history and its tangled geometry.

Unlike with most intercity train stations, where passengers flow between platforms and the street, the tracks at Union run parallel to its iconic head house, a configuration that significantly complicates the routes traversed by some 250,000 commuters every day. Once they reach the narrow island platforms, they find themselves standing beneath a grimy roof held up by iron latticework. It’s a stark structure – “a bit like a Meccano set,” El-Khatib notes.

Over the past five years, however, commuters have watched that utilitarian shed give way to a mesmerizing glass box suspended above the rails, supported by 24 pairs of angled I‑beam columns – a reference to two other local signature buildings: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Toronto-Dominion Centre; and the Sharp Centre for Design, by Will Alsop, a playful tabletop structure held aloft by off-kilter legs.

The 6,580-square-metre roof is just one part of a complicated, multi-phase expansion (and a bewildering architectural puzzle) transpiring at Union Station. The project – marred by budget overruns and delays and now estimated to cost $795 million – is slated for completion by 2016. Upgrades include the illuminated roof and an additional platform, for a total of 16, along with a refurbished subway station; and the Union Pearson Express, the first rail link between the downtown core and Toronto Pearson International Airport.

The heritage portion of the project will see the beloved Great Hall restored, and a retail concourse below the tracks that will provide multiple ways to connect with the high-rises that now surround the station. The vision also embraces an adjacent bus terminal and office complex, linked by two towers, with an elevated park built overtop of the tracks. Wilkinson Eyre of London and Adamson Associates of Toronto make up the design team for the development, and the project should break ground as soon as this year.

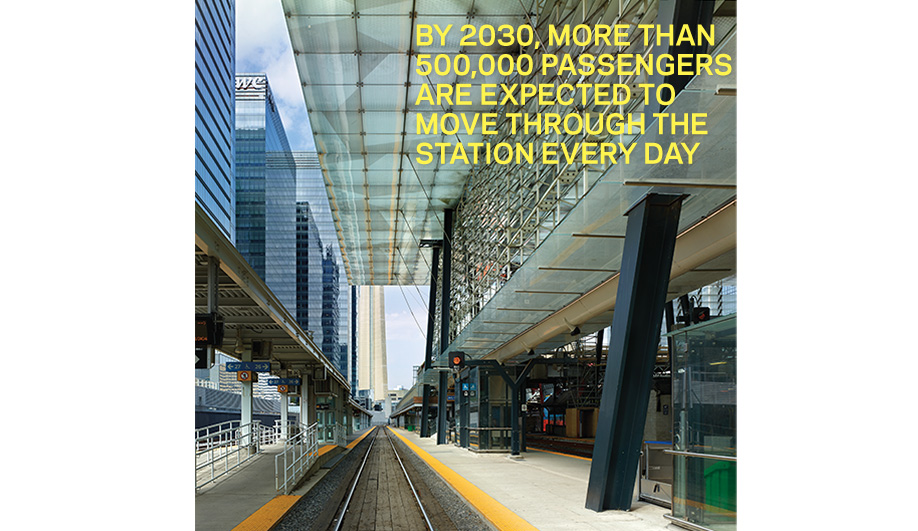

In short, the transformation is vast by international standards, with daily users expected to double to 500,000 by 2030. “I look at Union Station as the region’s most accessible spot,” says Bruce McCuaig, CEO and president of Metrolinx, the agency that oversees the rail lines. “It is the foundation of the regional transportation system. A significant part of the downtown depends on how we get people through that area.”

The first steps toward the makeover began in the mid-’90s and culminated in a controversial scheme to bring in a private consortium to revitalize and operate the station. City council canceled the plan in 2004, bringing in hired consultant Jennifer Keesmaat and a planning advisory to oversee a master plan that identified three key objectives: magnify the station’s role as a multi-modal transportation hub; elevate the importance of heritage preservation; and connect the station’s stately presence on Front Street to its dramatically changing surroundings.

“The building had to be permeable on all sides,” says Keesmaat, now Toronto’s chief planner. A key consideration, she adds, was restoring the “sense of arrival” to the big city. (See our interview with the Keesmaat here.)

The first phases are about to open in anticipation of the Pan/Parapan American Games, opening on July 10. Zeidler’s luminous roof will greet athletes and their fans with triple-layered translucent panels, dotted with opaque frits to create a pattern reminiscent of broken ice. Hundreds of angled glass louvres hang from the roof, forming an enclosure that allows natural ventilation while keeping out snow and rain. Eschewing the trend of colourful illumination, the internal trusses are wrapped in soft white LEDs.

One of the more workmanlike elements of the shed construction involves building the stairwells that connect the platforms to the extensive concourse two levels below. Millions of tonnes of fill have already been excavated to make room for 14,000 square metres of retail space. The big dig down, as it is called, has required some dramatic engineering feats, including cutting and elongating each of the 447 two-metre-wide concrete columns that support the tracks above.

Management of the concourse is in the hands of Osmington, a retail development firm controlled by David Thomson, scion of the Thomson media empire. Its aim is to make the new underground a destination unto itself. The plan, says vice-president of development Brad Keast, is for a retail environment that reflects the city’s diversity and provides venues for cultural programs and art events. The usual Starbucks will be there, but so will local retail offerings. There is talk of a fresh food market as the main draw, and some of the city’s top chefs have expressed interest in opening restaurants there. Idea Couture is handling branding, and Lightemotion of Montreal has been brought in to design an innovative lighting strategy.

Working with Partisans, a Toronto architecture firm run by Pooya Baktash and Alexander Josephson, Osmington hopes to break from the standard mall style. The corridors, including one of the main east-west spines that extends almost 200 metres, will be wider than in conventional shopping centres, and the hundreds of columns will accommodate seating, small stages and low-traffic spaces. “The idea is to create public areas,” says Josephson, adding that the concourse will service nearby condo dwellers along with travellers. “That’s a bold commitment on the part of the development, because it has architectural possibility.”

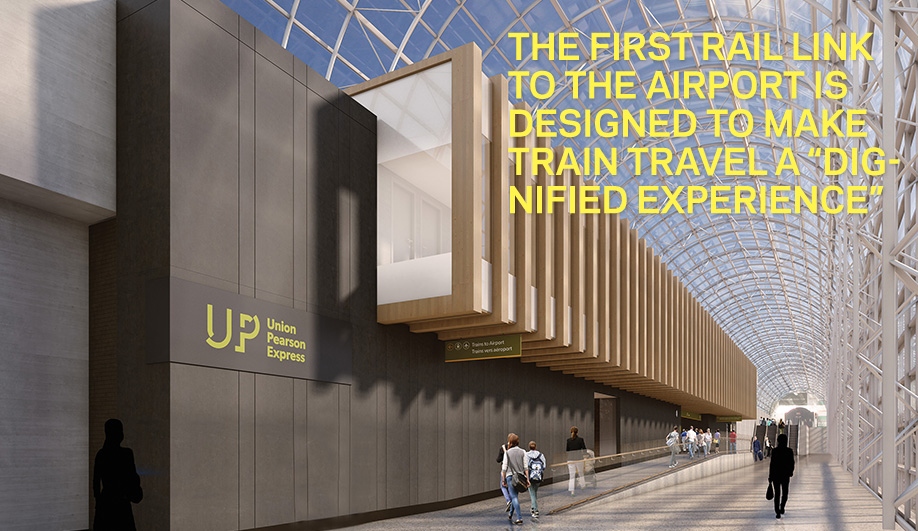

Its completion, along with a proposed restaurant in the Great Hall, is still a few years away. Much more imminent is the launch of the UP Express station, where 12 Sumitomo trains will move passengers to Pearson airport in 25 minutes. “This is the train at the end of the plane,” says UP Express president Kathy Haley, “an end-to-end experience.” Her team recruited Tyler Brûlé, founder of Winkreative, to brand the dedicated line as a means of delivering a convenient, memorable journey into and out of the core. Brûlé sees the service as “a showcase project for Canada” that will introduce the city.

The trains will be equipped with spacious seats, large windows, WiFi and other features. In terms of branding, he went with a northern Ontario palette of deep greens and browns, and for the uniforms he recruited men’s fashion designer Matt Robinson to come up with a similar earthy vibe. “This needs to be a very dignified experience,” says Brûlé, noting that the trip should present a smooth transition for travellers accustomed to business class air travel and VIP lounges. “It should feel grown up.”

Indeed, he says the refined ambience of the trains and the stations (starkly different from VIA’s well-worn look) represents “a bit of a call to action. It’s throwing down the gauntlet and saying, this is what rail transport can be.” El-Khatib says his team interpreted Winkreative’s directive in the station design by framing the elongated platform with a rib cage-like ceiling of exposed wood beams inserted between strips of glass. Light grey terrazzo is used for the floors.

What the new station lacks, however, is straightforward access to the street. At the moment, travellers must navigate confusing passageways before finding an exit. El-Khatib’s firm has suggested to Metrolinx a more efficient and visually appealing alternative, via an extended platform that would lead directly to Front Street. However, the idea is still in the works.

UP Express will invariably pump more bodies into Union Station in the coming years – about 2.35 million annually by 2018, according to Metrolinx’s projections – and the new GO Transit bus terminal on the precinct’s east side will add to the crowds. But those numbers will pale compared with the volumes anticipated when Metrolinx converts the GO train commuter service into a regional express rail system (RER) that provides all-day two-way travel, with electric trains running at intervals as short as 15 minutes during peak hours. More coaches are also being added. “We’re confident that we can manage capacity as we implement RER over the next decade,” says Bruce McCuaig. “What we are building now will be sufficient.” By 2030, the station will likely be operating on all cylinders. “The question is, how much can one building handle?” observes Keesmaat.

Metrolinx is already thinking about Union Station’s second century, and the need for shoulder terminals to service the burgeoning condo neighbourhoods and office/commercial clusters cropping up to the east and west. “That work still needs to be done,” says McCuaig. “It all has to be part of the network.”