John Lorinc looks at what cities around the world are doing to make quality shelter more accessible to more people – and how to avoid past mistakes while they’re at it.

When New York City mayor Bill de Blasio announced last year that he wanted the city to develop an astonishing 300,000 affordable housing units by 2026, he was directly targeting one of the most pressing problems of our urban age: the degree to which housing costs and a shortage of supply have become critical issues for the social sustainability of large, thriving cities. The need cuts right across society, from those on the lowest income rungs to young professionals and families that would once have been securely middle class.

As the heavyweight public housing projects of the 1950s and ’60s rapidly succumb to age, requiring extensive remediation or outright redevelopment, cities such as London, Amsterdam, Toronto and Vancouver are ramping up their production of new forms of affordable housing.

Architects in this field are keenly aware of the corrosive relationship between dehumanizing “prefabricated” design, poor planning and the social failures of past projects, as Dutch architect Hans van der Heijden observed at a Center for Architecture symposium in New York in February. The tragic blaze last year in London’s Grenfell Tower wasn’t just a wake-up call, but, as London architect Paul Karakusevic added, stark evidence of “market failure.”

Karakusevic, one of London mayor Sadiq Khan’s 50 appointed Design Advocates, is the co-author of the 2017 treatise Social Housing: Definitions and Design Exemplars and has co-curated a travelling exhibition documenting a range of recent projects. He has been at the forefront of a European movement to promote humanist, affordable housing design instead of the abstractionism and avant garde ideology of an earlier generation. This thinking is baked into London’s recently adopted municipal policies as well as de Blasio’s campaign, both of which foreground good design. As James Patchett, president and CEO of NYC Economic Development Corporation, writes in the report Designing New York: Quality Affordable Housing, “We strive to create a world where people can walk by affordable housing and not know it’s subsidized.”

What is affordable?

The precise definition of affordability in housing policy is notoriously elusive, but ambitious programs like New York City’s are meant to produce housing units geared to a range of low and moderate income levels as well as targeted populations such as seniors. The mechanisms used to set prices include traditional rent subsidies, various forms of mortgage assistance for affordable ownership, co-ops or other forms of non-profit projects, and apartment complexes constructed on city land.

This new era will be defined by master planning, extensive engagement with future tenants and the considered use of design review panels. Having consulted with leading minds in the field and having surveyed some of the most innovative projects worldwide, Azure has identified six key design principles that should be considered if the next generation of social housing is to be successful.

In many cities that are reconstructing and intensifying aging social housing complexes, a central development principle is to create projects with a mix of income levels and tenure types – everything from subsidized units to market rentals and condos. Affordable housing planners see this kind of mixing as a way of preventing the isolation and stigmatization that characterized so many social housing projects built in the postwar period, including London’s Kings Crescent Estate, a 1971 housing estate that was partially demolished in the early 2000s and is now being redeveloped – with an even split of affordable and market units – as a series of street-orientedmid-rises designed by Karakusevic’s firm, Karakusevic Carson Architects.

In Brooklyn, the 433-unit Navy Green complex takes the idea of mix one step further with a U-shaped development (designed by FXCollaborative with Curtis + Ginsberg Architects and Architecture in Formation) consisting of several housing types, from low-income and supportive housing to mixed-income rentals and condos to market-rate townhouses. That model has been replicated in France, where a 104-unit complex by agence Engasser + associés consists of three buildings – two of which contain privately owned apartments while the third contains social housing – sitting on a tight yet verdant plot in Ivry-sur-Seine. Finished last year, the buildings share an underground parking garage and a landscaped inner garden.

In Canada, meanwhile, Toronto’s 40.5-hectare Lawrence Heights complex – which is operated by the Toronto Community Housing Corporation (TCHC) and home to 3,700 low-income, mostly racialized tenants – is among the largest such projects in the country. The rehabilitation of existing subsidized units, now underway, will result in clusters of tall, mid-rise and townhouse-style buildings that reflect real integration, says Mark Sterling, a principal at Acronym Urban Design and Planning and one of the advisors on the project, which is being carried out by Metropia and Context and is expected to take years. KPMB Architects has designed one of the first components, a combination subsidized and market complex that wraps around generous shared courtyard spaces and includes a variety of clearly delineated private and public areas. “They wanted distinctive ways to provide territoriality that is recognized but not exclusive,” Sterling says.

As for the built form, KPMB has designed connected, U-shaped complexes with different tenure types in various wings. Under the agreement with TCHC, many of the ground-floor units will be rent-geared-to-income (RGI) rentals that replace grade-oriented subsidized units in the old Lawrence Heights. “They all have the same entry sequence, the same access to private and shared open spaces,” says Sterling.

TCHC is also the main player in Alexandra Park, a mixed-income neighbourhood in downtown Toronto where market condos and affordably priced units co-exist with RGI townhouses. Here, the corporation owns the land on which it has partnered with developer Tridel to build market condos, repair and upgrade existing buildings and construct 61 RGI townhomes. Toronto-based Teeple Architects was enlisted to design two phases of market condo buildings: SQ and SQ2. Both contain affordable housing – 10 units between them – either operated by TCHC through an RGI model or purchased by residents with assistance from the Affordable Housing Office.

Completed last year, SQ features family-friendly two- and three-bedroom units and connects to its surroundings with extended streets and parks – not to mention its dynamically jutting cube-shaped balconies. “The idea was to reflect [the diversity of the area’s architecture] with the jumpy, up and down, volumetric composition,” says Stephen Teeple. “We strongly believe in our mission to elevate the neighbourhood.” His firm was also behind the city’s 60 Richmond Street East Housing Co-op, a project that gave residents – primarily hospitality employees – free culinary training in its integrated restaurant and training kitchen as well as access to a sixth-floor terrace where they could grow their own herbs and produce. Which leads to our next lesson …

In hundreds of social housing complexes built throughout North America and Europe in the postwar era, non-residential uses, with the exception of small retail outlets, were effectively banished, creating a kind of monoculture that stood apart from increasingly mixed-use urban communities.

Many affordable housing projects now include grade-level retail space as a matter of course, with some providers negotiating community-benefit arrangements with municipal- or private-sector tenants to create jobs for social housing residents.

But some designers are pushing the principle of mixed use to the next level. For example, the Peninsula, a five-acre project in the Bronx, will combine subsidized housing, community and retail amenities, light industrial uses and public open spaces on the site of a notorious former detention centre.

Designed by WXY in conjunction with Body Lawson Associates and EKLA PLLC, the three-phase, US$300-million project will include a wide range of non-residential uses, from a school and a daycare to job incubators and a craft brewery. It is expected that almost 200 permanent jobs will be created at the Peninsula.

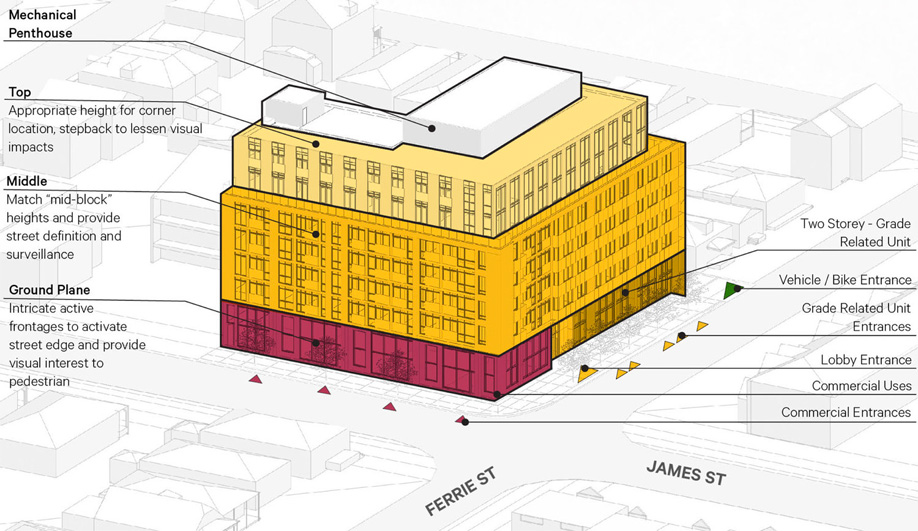

Many traditional affordable-housing complexes were highly inflexible, both in terms of design and with the restrictions imposed on the uses of open space at their bases. In Hamilton, Ontario, a proposed mixed-use affordable-ownership project – called 468-476 James Street North and designed by OFFICEArchitecture with SvN Architects and Planners – aims to replicate, within the context of a multi-unit apartment building, the flexibility of early-20th-century working-class neighbourhoods and their largely owner-built homes.

Drew Sinclair, SvN’s managing principal, says the idea is to allow owners to purchase “lots” or “bays” and assemble apartments of varying sizes (studio to three-bedroom) rather than limit residents to a series of pre-configured floor plans. In addition, the building will be constructed with modular walls and concrete columns instead of sheer walls, enabling owners to add to or subdivide their units as their life circumstances change. The modularity gives households making as little as $25,000 a year the opportunity to buy in.

Nor is flexibility just a financial or spatial feature. Tiffany Duzita, director of the Community Land Trust Foundation of B.C., which launched a plan in May 2018 to co-develop more than 1,000 affordable rental units in Vancouver, points to a proposed 58-unit Vancouver co-op that would enable residents over 55 to age in place. The floor plans for the building and for individual units, designed by dys architecture, reflect universal design principles and allow for the use of mobility equipment as necessary; the building will even be fitted with charging stations for electric scooters.

Wohnprojekt Wien – a Viennese co-op situated near a former railway station – was conceived earlier this decade by Einszueins Architektur as an “edible landscape” that combines sustainable design with local food grown onsite. Located close to transit and serving tenants who mostly avoid car ownership, the project includes a bevy of food-related elements – including community gardens, food-storage rooms and a food co-op – as well as a shared library, sauna and workshop. The inclusion of such amenities within affordable-housing projects mirrors those in market buildings. But housing agencies and developers are also adding larger stand-alone community facilities to revitalized housing developments. One example is the Daniels Spectrum, an arts and community complex by Diamond Schmitt Architects that anchors the Regent Park redevelopment in Toronto.

What’s also clear is that the design of many next-generation affordable-housing projects emphasizes links to surrounding areas and uses built form to achieve this integration. The New York City affordable-housing design guidelines, for instance, call for ground-floor treatments, windows, facades and materiality that complement adjoining buildings. The tower-in-the-park approach favoured in so much postwar social housing has, in effect, given way to more street-oriented site planning.

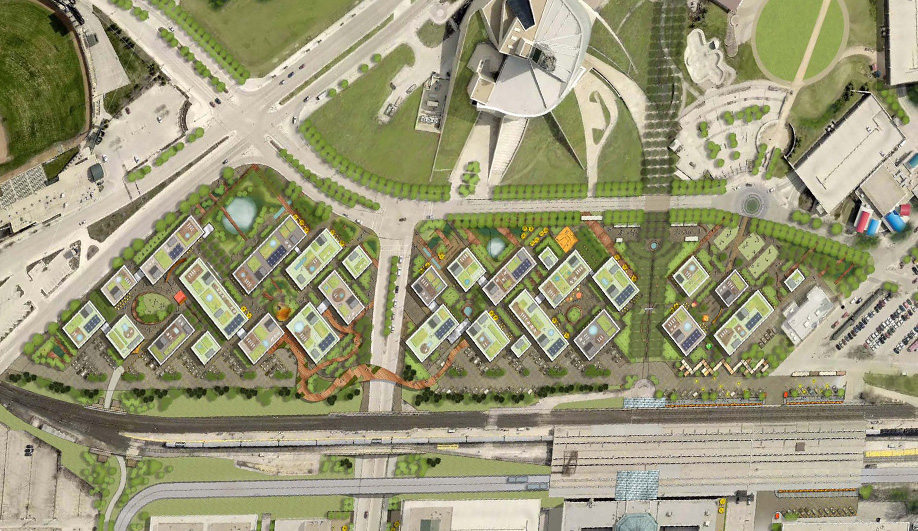

In fact, some affordable-housing designers are also revisiting issues of height and massing. Johanna Hurme, a principal at 5468796 architecture, points to the 20-year mixed-use master plan for Railside at the Forks, an 11-acre site near the Canadian Museum for Human Rights in Winnipeg. Instead of a handful of high-rises, Hurme’s firm has proposed 35 mid-rises. Built on a granular urban street grid, the structures aim to foster livable connections with commercial and public spaces in the Forks.

Dutch designer Van der Heijden points out that the height debate has largely been settled in cities like Amsterdam and Berlin, which opt for the urbanizing nature of mid-rise apartments. “In terms of density, a high-rise doesn’t do a lot for you,” he says.

If the harsh lesson of earlier public-housing projects is that you get what you pay for, then it’s increasingly clear that sustainability, broadly defined, has emerged as a driving force in the development of new versions. Drew Sinclair of SvN points to the reuse of fallow church-owned real estate as an example of how to reduce the pro formas on affordable-housing projects; the land costs are often negligible, and the savings can be applied to preventative maintenance.

Likewise, energy efficiency through architectural choices such as passive design, heat recovery systems, engineered wood and thermal windows reduces both the upfront capital costs and the ongoing operating and maintenance expenditures.

But Karakusevic points to another historical dynamic that informs long-term maintenance. When many of the British estates were built, the tenants were almost all employed in the booming postwar industrial economy. By the seventies and eighties, when deindustrialization had become widespread, those buildings increasingly evolved into multi-generational welfare traps. That meant lower rental incomes, vacant units and a general lack of political will to re-invest.

As Karakusevic explains, the Thatcher-era “right to buy” policy for council housing led to many units migrating into private ownership; these units have accrued value over time, and their residents have become more vocal. When anything stops working or goes wrong, Karakusevic says, they’re on the phone to the local council right away – a dynamic that has forced traditionally unresponsive housing-department officials to address problems in real time. “There’s an awareness now that you have to do all these things,” he says.

The demands for rapid repairs mean that small problems don’t fester or become large, expensive ones. Improved long-term maintenance, in other words, is not just engineered into these housing estates; it’s the product of social organization that didn’t exist when the housing first deteriorated.

According to Austrian architect Markus Zilker, a principal at Einszueins Architektur, social housing is available to about 80 per cent of the population of Vienna, where almost three quarters of the housing stock is subsidized – a model of “housing sanity,” as The Globe and Mail noted when a travelling exhibit of the Austrian capital’s housing model came through Vancouver last year.

The Viennese social-housing model, which prevents speculation and caps rents at 30 per cent of a resident’s income, dates back to the 1920s, a period when the city deployed property taxes, rent-control legislation and restrictions on land speculation to counter decades of hidden poverty in the Austro-Hungarian empire. As University of British Columbia urban-design professor Patrick Condon noted recently, Vienna learned never to sell municipally owned real estate; indeed, its long history of land banking has allowed non-profit housing organizations to thrive.

Vienna also receives national and regional government grants amounting to about $900 million annually; it uses the funding to construct about 9,000 new units per year. New housing projects, notes Katharina Bayer of Einszueins Architektur, are subject to reviews that encourage developers to see beyond the price of subsidized housing.

Few other cities have aligned their architecture, funding models and public attitudes quite like this. But as the cost of living and the cost of housing skyrocket in major cities globally, municipal governments are revisiting the imperative to build high-quality social housing. In a number of cities, planning policies such as “inclusionary zoning,” which compels private builders to add a specified amount of social housing to residential projects over a certain size, are bringing new affordable units onto the market. And in Vancouver, one of Canada’s most treacherous markets, the city’s housing authority teamed up with New Commons Development (a developer of non-profit housing) and B.C.’s Community Land Trust to build more than 1,000 new units for people earning between $30,000 and $80,000 a year. Encompassing several locations, the ambitious deal was described by mayor Gregor Robertson as the “largest single investment” in community housing in Canada’s history.

Of course, these kinds of positive examples depend heavily on political will and on an awareness that governments need to use mechanisms other than market forces to address urban housing affordability. As Mark Sterling says, “Unless we can break the economic model down, whether through inputs on investment or subsidies, we’re going to have a hard time to get any of this stuff to happen.”