I.M. Pei, one of the world’s most celebrated architects, is marking a major milestone today. Ieoh Ming Pei was born April 26, in Guangzhou, China and moved to the U.S. at the age of 17 to study at the University of Pennsylvania. After a brief stint in the engineering department at MIT, Pei returned to architecture there and then at the Harvard Graduate School of Design.

He launched his career in 1948, going to work not with an architecture firm, but a real estate developer. A surprising move for such a promising young architect, it set the tone for a career that has been equally defined by unpredictable choices and strict geometries. His work, first with Webb and Knapp, and then with his own firm (which eventually settled on the name Pei Cobb Freed & Partners) stretched over eight decades and around the world.

Pei’s global reach is reflected by events honouring the Pritzker laureate that take place not just today, but all year long. In Washington, D.C. talks are being presented at his renowned National Gallery East Building. Harvard GSD has the symposium Rethinking Pei on the books for October, and the same presentation will run in Hong Kong this December. In Suzhou, China, where Pei’s Suzhou Museum is a local landmark, a month-long series of celebratory online and offline events are being presented by the local tourism board. At Azure, we’re marking the centennial with roundup of a dozen of our favourite I.M. Pei projects.

Mesa Laboratory of the National Center for Atmospheric Research, Boulder, Colorado (1966)

During his time with Webb and Knapp and his early years with his own firm (during which he still worked regularly with the real estate developer) Pei designed many city buildings, carefully inserting his own work into existing urban contexts. After breaking ties with Webb and Knapp, the Mesa Laboratory brought his first opportunity to work within a natural landscape. Taking inspiration from the Anasazi cliff dwellings of the region, he blended local aggregates into the building’s concrete walls to help the towering structure to blend into the adjacent hills.

The distinctive form of this concrete structure is often compared to that of a giant sewing machine. Shaped to preserve views of Cayuga Lake, the building’s cantilevered fifth floor floats above a ground-level sculpture garden.

A return to tight urban sites, the gallery is positioned on a trapezoidal plot, sitting at an angle on Pennsylvania Avenue on the north side and alongside the National Mall on the south. Pei responded with a series of acute and obtuse angles that characterize both the exterior and interior. Dust from the Tennessee marble of the neoclassical West Building was added to the concrete mix for the East Building’s interior walls, helping tie the two aesthetics together.

In 1964, Pei was handpicked by JFK’s widow, Jacqueline Kennedy, to design a library that would serve as a memorial to the assassinated president. But it would be 15 years before the project would see completion. Setbacks included changes in site, and financing issues. As a result, Pei had to alter his design. Turning once again to economical concrete, rather than the elegant stone he’d hoped to use, Pei intersected a stately, triangular tower and a low, cylindrical volume with an airy glass pavilion.

A radical departure from the modern aesthetic he’d become known for, the architect’s traditional twist for this project shocked critics. For Pei’s return to China, he wanted to respect the location, and built this 3,690-square-metre hotel in five sections: a main four-storey building with four smaller wings branching out, in order to avoid cutting down any of the trees surrounding. Gardens and courtyards are inserted within the building’s recesses.

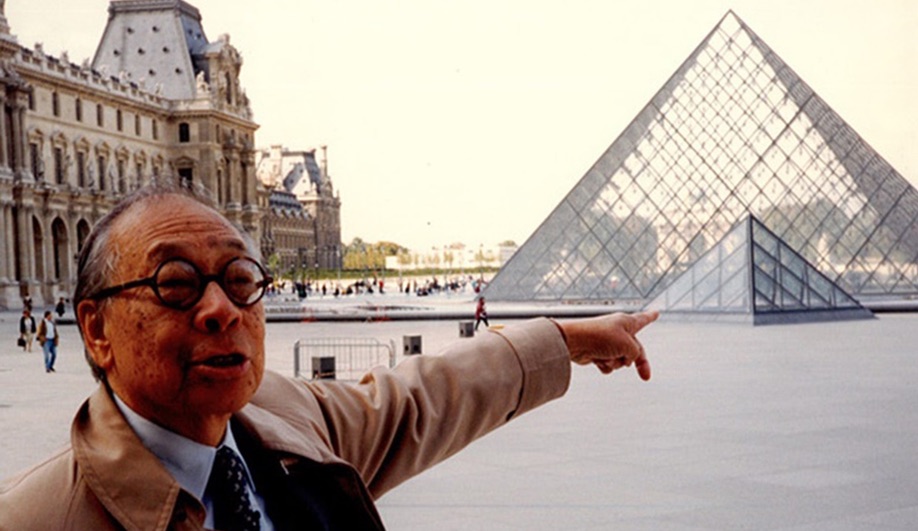

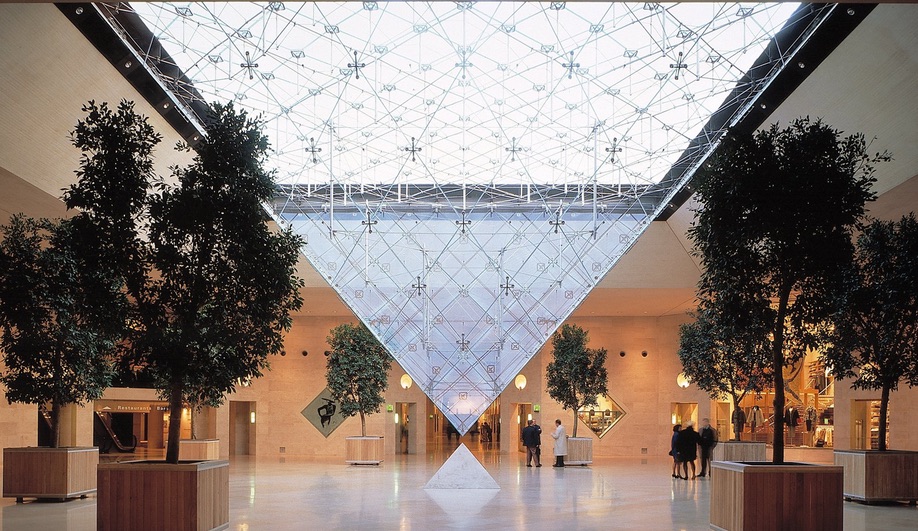

Triangles and pyramidical forms had long been a theme in Pei’s work and this intervention in the courtyard of the Louvre museum is the ultimate culmination of this leitmotif. The original pyramid, and the underground lobby below, were constructed as a new main entrance for the institution, after the original entrance could no longer accommodate the volume of visitor traffic. The steel and glass pavilion is constructed from 673 rhomboid and triangular glass panels, and covers 1,000 square metres at its base. La Pyramide Inversée, an inverted pyramid skylight, was later added to the Carrousel du Louvre, to help point visitors to the entrance lobby from within the underground shopping mall.

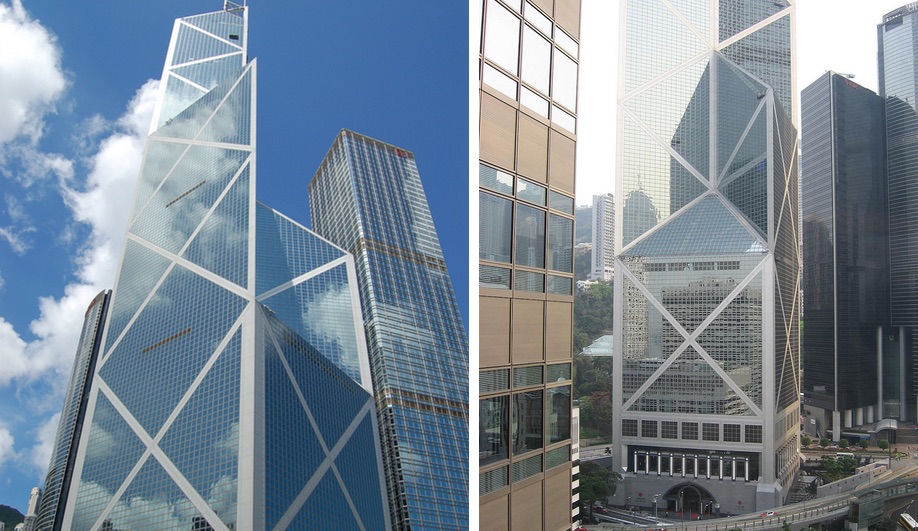

Meant to evoke the structure of bamboo, this four-section, 70-storey tower cuts an imposing figure into the Hong Kong skyline. At ground level the reflective glass-clad tower stands as a cube, with triangular quadrants gradually removed as it ascends, forming a uniquely faceted structure. The sharp and sloping angles helped the building meet the city’s uncompromising requirements for wind resistance.

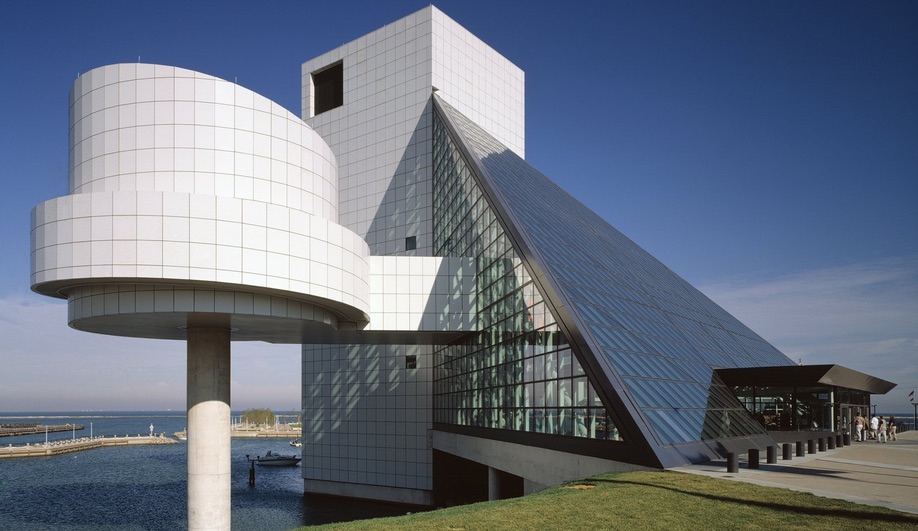

Pei puzzled the critics again when he accepted the commission for this shrine to rock ‘n’ roll, which many considered a bit low-brow for such a renowned architect. Endeavouring to echo the energy of the music it would represent, Pei created one of his most unique buildings, which New York Times architecture critic Herbert Muschamp referred to as having “an Elvis-like swagger of its own…a swivel-hipped apparition in metal and glass.”

Gliding through the forest in the Kyoto mountains, the Miho Museum is a stunning reward at the end of a journey that includes a sloping path, a tunnel, and a bridge. Much of the 17,400-square-metre building is underground, providing optimal exhibition space for a large collection of Asian and Western antiques, with minimal interruption of the natural landscape. Familiar angles are seen in the steel and glass roofs, though for this project I.M. Pei was able to use Magny Doré limestone from France, as well as coloured concrete.

Museums had become a specialty for Pei by the time he took on the MUDAM, which came with the challenge of incorporating the historic ruins of Fort Thungen into his design. The new building emerged as an extension of the old – a jagged, limestone-clad volume rising above the walls of the ancient fortress. “What interests me is how to harmonize the past and the present so that they mutually reinforce each other,” says Pei of the project.

The significance of this project convinced I.M. Pei to come out of retirement and spend six months touring the region and studying the mosques of Spain, Syria and Tunisia. Originally slated for a site along Doha Bay, Pei initiated a new plan that would see a new island built to accommodate the museum. The sandy Middle Eastern landscape inspired this pale monolith, which is all about procession: from the approach from the Corniche road, to the staggered twists of the stacked volumes that compose the main section.

The most recently completed project with I.M. Pei’s stamp on it is this museum, which is actually designed by the firm founded by his sons Chien Chung Pei and Li Chung Pei, Pei Partnership Architects, in association with I.M. He reportedly was responsible for selecting the prominent site, which allows the asymmetrical structure, clad in aluminized steel, to be seen when arriving in the city on the ferry from Hong Kong.