Olafur Eliasson-mania has touched down in Montreal. The Berlin-based installation artist visited the city in June to give a free talk a few days ahead of his first solo exhibition in Canada. As a prelude, a jostling mob of hundreds of latecomers caused a ruckus when they discovered that they weren’t going to get into Concordia University’s 400-seat D.B. Clark Theatre, which was already packed to the rafters. The situation at the door spiralled into a security incident when a handful of gatecrashers forced the museum staff to shoo them from the house.

Mercifully, there’s still plenty of time to see Eliasson’s Multiple Shadow House at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal (MACM). This tidy and fun retrospective runs until October 9, 2017, and features six works spanning 1993 to 2015, including Your Space Embracer (2004), a new addition to the MACM’s permanent collection.

In recent years, the artist has skyrocketed to near-household notoriety by making worldwide headlines with Ice Watch (2015). During the United Nations-led talks on climate change in Paris, he unveiled a collaboration grouping of 12 “icebergs” – monumental blocks of ice farmed from a fjord in Greenland and left to melt in Place du Panthéon.

“Smaller people they are very fast in understanding that we need to take in the world by touching it, holding it or hugging it,” he says, standing on stage in front of a slide of Parisian youth interacting freely with the icebergs, and perhaps defending a small boy who is licking one of the blocks of ice.

In 2014, Eliasson won the Eugene McDermott Award in the Arts from MIT, one of the most prestigious and generous prizes in North America that comes with a US$100,000 grant. About a decade prior, more than two million visitors flooded the Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall in London for The Weather Project (2003), the Danish-born artist’s most popular installation for a museum ever. Since then, revisionists have increasingly ascribed The Weather Project to climate change – which it wasn’t about initially, but is now.

As a result of this string of accomplishments, as well as Eliasson’s deft use of elemental materials and naturally occurring phenomena, he is now, if not the world’s foremost contemporary artist, the leading artistic voice of Anthropocene-activism.

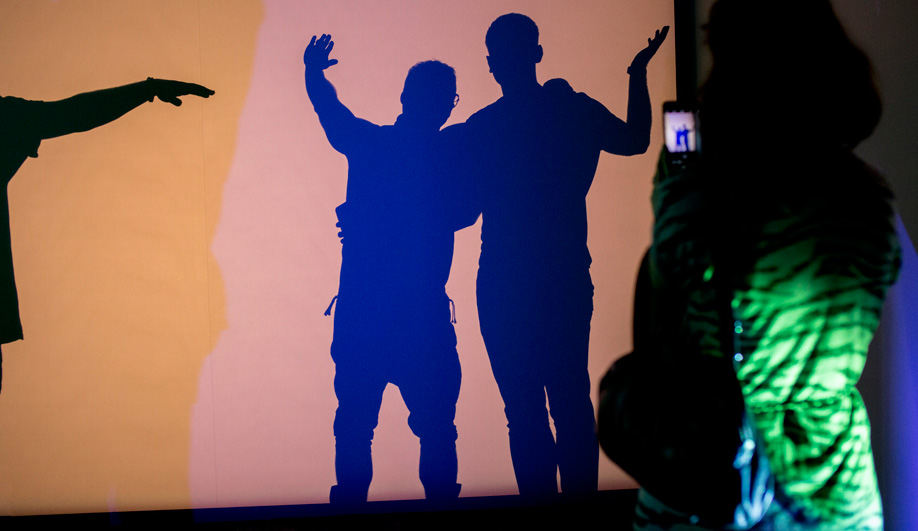

For those who did score a seat inside Concordia’s theatre, Eliasson dished on how to get the most out of the MACM show’s namesake installation. “What’s interesting is having your shadow blend with someone else’s. They become a collage on the wall.” Multiple Shadow House’s wooden framing supports taught, white screens that enclose the rooms. Select walls display visitors’ colour-split shadows when they move in between the screens and the banks of light sources scattered about the floor with varying arrays of halogen bulbs and white, orange, red, blue and green films. “I think that has a certain potential,” he continues, “It might amplify the chances that you may meet that person and your shadow dance may subvert the museum’s otherwise high degree of social control.”

As is the case with the two interactive aquatic installations that bookend the show, Big Bang Fountain (2014) and Beauty (2013), Eliasson is the first to admit that the singularity of his work is easy to miss: at times just a drizzle, a sound or a temperature. “When you walk into a room and say, ‘There’s not much here,’ your presence becomes more important,” he explains. The viewer’s interaction with an installation is the secret sauce that completes Eliasson’s works. He is asking admirers to see the invisible, including “seeing themselves seeing.”

This restraint in creating installations is geared towards combatting a generalized numbness and tantalizing viewers’ lizard brains into a state of hypersensitivity. This heightened awareness brought on by his minimalist approach may lead to new sensations. “What’s exciting is that sometimes you feel the world pushing back,” Eliasson says.

Newcomers, to Eliasson’s work could accuse him of being overtly political and an ecological opportunist. Yet, as the earlier works in Multiple Shadow House show, his art has always been spring-loaded. And they are also political – just not in the way you’d think.

In these fractious times, to Eliasson, gallery spaces are nothing less than models for the parliaments of the future due to their ability to accommodate difference. “The museum hosts the opportunity for people to be together without being the same. That’s not something we can take for granted,” he says. “It’s a space in which we can share or negotiate something – not necessarily verbally – and still not necessarily agree. I like this idea. I can say ‘I like the yellow colour.’ And the other person can say ‘I really thought it should’ve been red,’ but we can still be friends.”