What emerges at the Venice Biennale, curated by Pritzker laureate Alejandro Aravena – and featuring 88 firms from 37 countries – is a convincingly hopeful picture of architecture with a more relevant scope, whether in the developed or developing world.

What is the front? Or, where is the front? The curator of the 15th Venice Architecture Biennale, Chilean architect Alejandro Aravena, defines the battle “to improve the quality of the built environment and consequently people’s quality of life,” and in his exhibition, Reporting from the Front, the fronts are many and widely dispersed.

To explain his vision, Aravena recounts the story of legendary travel writer Bruce Chatwin’s encounter with German archeologist Maria Reiche in a Peruvian desert. She was carrying an aluminum ladder she was using to study the Nazca lines. From the ground the stones seemed random, but from atop the ladder they revealed the shapes of large-scale plants and animals. Chatwin’s photo of Maria Reiche scrutinizing the horizon from atop the ladder has become the pictogram for this biennale.

The photograph is a metaphor for the curator’s intention to reveal a composite picture by pulling together accounts from those pushing forward architecture’s frontlines. Aravena – this year’s Pritzker Prize winner and renowned for his work on low-cost, incremental housing projects – is advocating for a new scope for architecture that goes beyond cultural and artistic dimensions to include social, political, economic and environmental concerns. It is those areas, where the battle for “quality of life” is being advanced, that drive Aravena’s biennale.

Eighty-eight firms and entities from 37 countries are participating in Reporting from the Front (50 are newcomers to the Biennale and 33 of the architects are under 40). Aravena’s exhibition spreads over the Arsenale – the former Venetian shipyards – and the central pavilion of the Giardini, where the historic national pavilions are also located. Not all of the 65 national participations address the curator’s theme.

In the enormous halls of the Arsenale, the awesome setting evoking the great power that once emanated from here, one biennale can seem like another. Venice is a selfie city, image is king, and architecture is among its most loyal subjects. This exhibition is about ideas, yet it doesn’t shy away from using images based on conviction to galvanize attention. In the entrance to the Arsenale, twisted metal studs are suspended from the ceiling and the walls are formed of stacks of drywall fragments, all derived from construction debris retained from the previous year’s art biennale. The effect is no less stunning for its origin, and at the same time manages to transmit one of Aravena’s battle cries, “against abundance: pertinence.”

That and other pithy messages emanate from the installations that follow, beginning with an object lesson by Al Borde Arquitectos from Ecuador, demonstrating the modest cost of some of their completed works with bags of euro cents deposited inside square metres outlined on the floor. Juxtaposing their eight smart, community-focused projects is a ninth square, overflowing with coppers, representing the average cost of construction for a project in Venice.

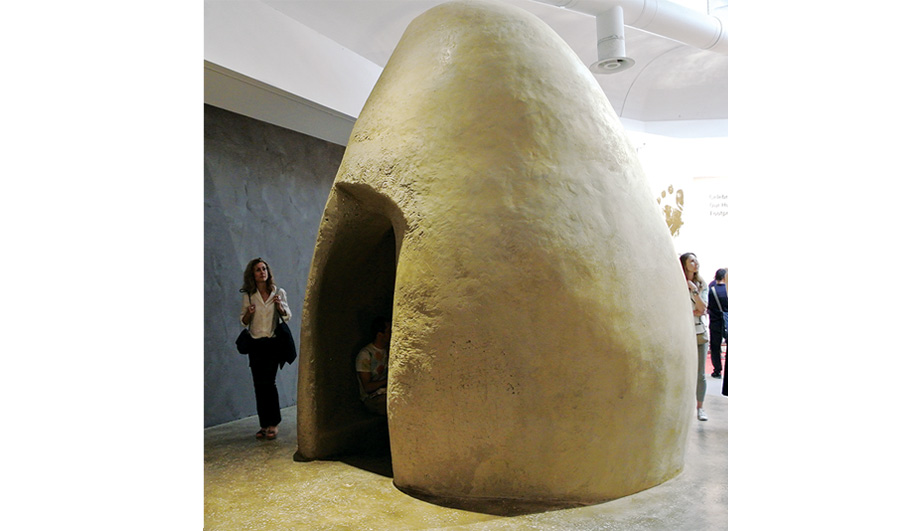

Money does not make good architecture. Strategies for overcoming financial constraints include participation – buildings designed to be constructed or hacked by their users; cheap and abundant local materials, such as mud and bamboo; exploiting synergies to achieve results that would otherwise not be possible.

This is no starchitect’s biennale, nor is it an earnest emerging world biennale. The Venice Biennale has deep connections to established institutions, educational and otherwise, and some of the participants here have intersecting roots (Aravena’s Pritzker implies affiliation with a global establishment, and this can only help his cause). But, still, it is rewarding to see expressive modern forms created with extremely limited means, employing local materials and resources. Two impressive examples include Anupama Kundoo Architects in India and Studio Anna Heringer in Bangladesh, who both make modern forms out of mud. Another is Simón Vélez in Colombia, a long-time advocate for the validation of bamboo as a modern building material, and who calls for more vegetarianism in architecture.

The curator has also made room for work that he defines as “good” architecture – where the architects remain true to a vision, despite financial and other pressures to compromise. Among these is Marte.Marte Architects of Austria, whose infrastructure projects are haikus of essence and restraint, refreshingly free of flourish.

This report is a fragment; Reporting from the Front is huge, multi-layered and pretty much impossible to sum up. Still, what emerges is a convincingly hopeful picture of architecture with a more relevant scope – whether in the developed or developing world.

Of the national participations that followed Aravena’s theme, Germany stands out for Making Heimat, dedicated to the pressing issue of providing support for recent immigrants. With over a million refugees flooding into Germany last year, ideas for effective integration and accommodation are crucial. The Netherlands offers Blue, a study on how the base infrastructure created for U.N. peacekeeping missions can become a catalyst for development in strife-torn areas.

It is a good year for Canada, with two excellent installations. The University of Waterloo’s The Evidence Room, in the Arsenale, validates Professor Robert Jan van Pelt’s life work documenting the architectural underpinnings of the genocide machine that was Auschwitz. And the official Canadian entry, staged outside the national pavilion in the grounds of the Giardini, takes on the complicated theme of Extraction.

Led by landscape architect Pierre Bélanger, it calls out Canada as the world’s leading mining power with the attendant responsibility for the impact of global resource extraction; it also petitions for an end to the colonial mentality that results in displacement of indigenous and other populations.

Some reports will upset the status quo. But if and when architecture takes on the battle for quality of life, that is the expected, indeed, the desired, outcome.

The 15th Architecture Biennale continues in Venice until November 27, 2016.