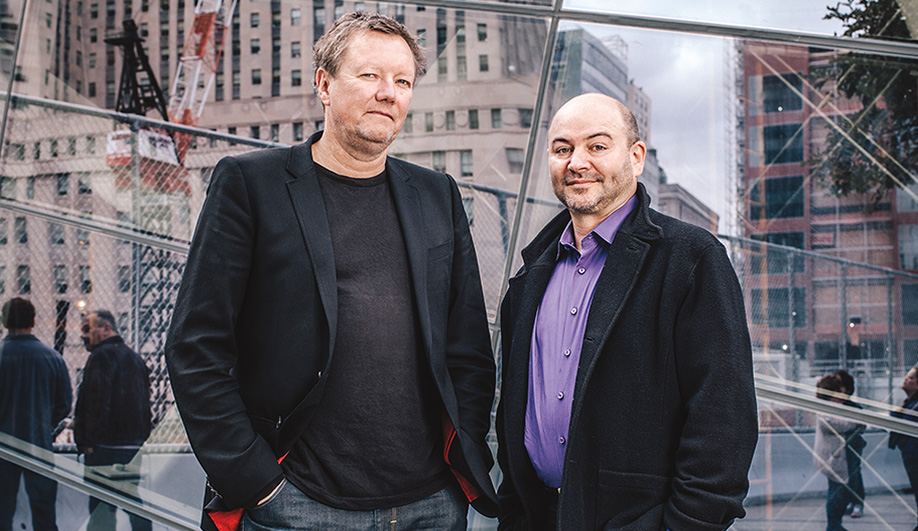

As Craig Dykers and Kjetil Traedal Thorsen inaugurate a new outpost in California, their in-demand studio has undoubtedly hit its stride with an impressive list of commissions, both newly built and underway. What makes it the firm of choice for projects of every scale?

On a Friday night in San Francisco, Craig Dykers stands on a plastic chair beneath a spinning disco ball, beer in hand. Wearing a green army jacket and his trademark puckish grin, the founding partner of Snøhetta is in California to christen his firm’s new West Coast outpost. “A number of international architects have made one important building in this city, then returned home,” he announces to the crowd of fellow Snøhettans, journalists and friends, all jammed into the one-room office on 8th Street. “We’re planning to stay close to San Francisco.”

On the wall behind him is a massive white model, its uneven surface defined by long grooves and ridges. It’s a sample of the exterior panelling that will define Snøhetta’s own “important building,” the SFMOMA expansion. The point of Dykers’ toast is to instill the notion that once the landmark project is completed in 2016, his firm will be staying put. “We want to have a big influence here,” he tells me later, after the speech ends and the crowd disperses.

Such a commitment might come off as boastful, even a bit cocky. But neither Dykers nor his partner, Kjetil Traedal Thorsen, shy away from speaking publicly about their love of big visions and bold ideas. One minute of conversation with either of them is enough to leave the impression that you are speaking with the smartest guy in the room – and one who knows it, too. They are intellectuals in the architecture world, giving lectures around the globe, but they don’t design unbuildable, pie-in-the-sky hallucinations.

That ability to blend showmanship with conviction – to make clients and juries believe that a proposal is not just beautiful but realizable as well – is key to Snøhetta’s meteoric success. Now at work on four projects in the San Francisco Bay Area alone, the firm is also designing an opera house in Busan, South Korea; a museum in Guadalajara, Mexico; a massive cultural centre in Saudi Arabia; and the headquarters for Le Monde Group in Paris.

Founded in 1989, Snøhetta now employs 150 practitioners and operates out of two main offices, with Thorsen based in Oslo and Dykers in New York. Other colleagues are scattered around the globe, in Austria, Saudi Arabia and Singapore. “When we set out, we had a 30-year plan,” says Thorsen, speaking by phone from a ski cabin in Norway. “We envisioned 10 years of establishing the firm, 10 years of consolidating it, and another 10 for building stuff. We’re not far off.”

The partners have managed their growth by staking the firm’s name (Snøhetta is a mountain in Norway, and the home of Valhalla in Norse mythology) on architecture that is less gestural and formalist; less top down and trademarkable than the so-called starchitecture that has defined much of the past two decades. “It’s true, a lot of our buildings look different from one another,” says Thorsen.

If they deny their participation in the starchitecture wave, that doesn’t mean they’re not stars in the eyes of many. In 2009, the firm won the international competition to design Ryerson University’s Student Learning Centre, located on a tight lot in Toronto 1,920 square metres in size, and hemmed in by shops and restaurants along a busy street. Early on, Dykers visited the proposed site, which was still occupied by the iconic Sam the Record Man store, and he noticed its appeal. “Even in the winter, that stretch of Yonge Street was populated at night with people playing chess under the neon lights of the Sam’s marquee,” he says. “With our roots in the northern hemisphere, we’re acutely aware of the importance of daylight, especially in cities.”

The 10-storey centre, open since March, has already left an impression on students and passersby. Its triple-glazed walls are dappled with a digitally printed white pattern baked onto an inner layer, to help control daylight levels; and each floor is accented with a distinctive colour scheme and spatial orientation, to create variation within what is basically a cube. On various floors, students have the option to study in quiet zones, in breakout areas, or within glassed-in study rooms with whiteboards painted on the walls – perfect for working out formulas or generating lists.

The sixth floor, nicknamed the Beach, is one space that takes advantage of a double-height ceiling and a sloping floor, which leads to a view southwest along Yonge Street. Amphitheatre-type steps and terraces are clad in maple, evoking sand, while eccentric rings of overhead tube lighting recall the sun. The casual vibe, and ample room for lounging on the soft seating that is scattered about, has made the Beach the most popular spot on campus.

The more dramatic incision into the centre’s boxy form is at the main entry, where a corner is cut away to create a geometry that draws pedestrians up the stairs and into the public atrium. It is clad in a 3‑D pattern of folded, iridescent sheets of blue aluminum, and it acts as a beacon, capturing light and summoning attention. “The line between where a building ends and where landscape begins is not always clear, and our projects often form a dialogue across those disciplines,” says Dykers.

Snøhetta understood that Ryerson wanted more than a building; it wanted a piece of architecture that would connect the once-anonymous campus to the busy urban street, one that would signal a new era for a university with ambitions to become a leader in cutting-edge technology and entrepreneurship. “Somebody might have a great idea, but can they execute it?” says Sheldon Levy, the university’s president, who was involved in the competition. “Snøhetta brings together that infectious passion and edginess with a reputation for being able to deliver.”

Negotiating complex urban spaces also lies at the centre of the SFMOMA extension. Working in the high-rise-heavy district known as South of Market – and retaining Mario Botta’s original 1995 low-rise brick structure – Snøhetta carved out a second entrance into an alleyway between Howard and Natoma Streets and built upward. The tower, clad in those rippling, fibre-reinforced polymer panels on display at the firm’s new office, feels almost organic against the rigid lines that surround it. Some 700 panels are finished with a shimmering quartz aggregate designed to catch the California sunlight. From a distance, its form evokes a rolling wall of fog or a chiselled iceberg.

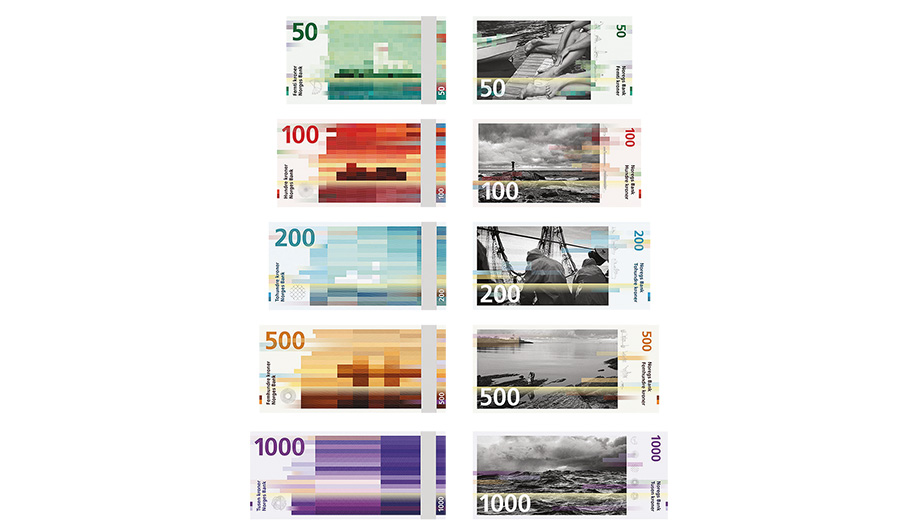

The firm’s sense of conviction led to a number of high-stakes commissions, from the National September 11 Memorial Museum pavilion and a reimagining of Times Square in New York, to the winning design for Norway’s new banknotes. Quite literally, their graphic sensibilities will be printed on Norwegian kroner, beginning in 2017. What keeps Snøhetta grounded is its range. “We aren’t aiming to be bespoke tailors of architecture for the rich and privileged,” says Dykers.

Whether for a system of public benches in Guatemala City or a temporary garden pavilion in Quebec City, the more intimate projects accomplish two goals: they prove that big ideas can succeed in small packages; and, coupled with a tendency to integrate public access spaces into private buildings – SFMOMA and Ryerson University included – more modest projects cast the firm’s intellectualism as both pragmatic and attainable.

Snøhetta’s first completed building in Canada, the Isabel Bader Centre for the Performing Arts at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, illustrates this versatile approach. The 566-seat concert hall is the most striking element of the multi-purpose arts facility on the shore of Lake Ontario, completed last fall on a $45‑million budget, and in partnership with N45 Architecture of Ottawa. Snøhetta carved a few corners off the main room to give it better acoustics and a more organic feel. The walls are clad in CNC-cut MDF panels veneered in five distinct shades and types of wood. It gives the effect that one is standing amid an excavated limestone pit, with stratified layers visible all around. The seats, in naturalist shades of green, evoke still water at the bottom of a quarry. Standing on the stage and taking it all in, one sees clearly that Snøhetta has mastered the art of capturing a feeling of time and place.

The problem, if you can call it that, is finding the similarities between one structure and another, the gestures that say, yep, that’s a Snøhetta. It’s not a designer suit with the logo stitched on the lapel. Rather, the firm’s trademark is negotiating the gap between big ideas and finished projects. One senses that Snøhetta’s dedication to methodology rather than style is what will endure. “It’s nice to have a vision of Snøhetta as something that will last longer than us,” says Thorsen. “We’re now in a situation where we have to think of extending our practice to the next generation.”

As the launch party at the San Francisco office moves deeper into the night, and the sounds of Swedish techno plays in the background, Dykers wanders over to a food truck parked along the sidewalk on the street outside. The truck, Señor Sisig, fuses Filipino and Mexican cuisines. “I asked my local food insiders what we should get, and this was the consensus,” Dykers says, biting into the soy-marinated pork loaded onto a corn tortilla. Standing in the pink glow of a neon Ø that illuminates the office’s front window, he casts the silhouette of a man still hungry to leave his mark on the world.