All work and no play makes jack a dull boy. Granted, Jack does not lack for innovative toys and gadgets. But what Jack really needs is better playgrounds. These days, reality is exchanged for a simulation of reality, and the sandbox is abandoned in pursuit of the virtual. Cognitive scientists, however, are finding that the unstructured activity children engage in at the playground fosters the social and intellectual abilities they need to succeed in life. Monkey bars and swing sets present opportunities to develop new skills, encourage autonomous thinking and promote flexible problem solving – but they also shape the brain. This is good news. With technology taking over so much of our lives, increased pressure on children to compete academically at a much younger age, and helicopter parenting restricting play for fear of potential danger, many experts – such as David Elkind, psychologist and author of The Hurried Child – are drawing attention to the “reinvention of childhood.” It is time we also reinvent the playground.

This renewed awareness has found an unlikely champion in New York archi-tect David Rockwell. Best known for his glamorous restaurant and hotel in-ter-iors for such clients as W and Le Méridien, he has turned his attention to entertaining a younger crowd with Imagination Playground, a kids’ park whose chief conceit is piles of large blue foam shapes – a sort of Tinkertoy on steroids.

A recent visit to Imagination Playground’s flagship park, in Manhattan’s South Street Seaport, reveals tykes unabashedly co-opting fellow collaborators to build fire trucks and forts. “We get to dream, and everything we dream will come true,” exclaims one little girl while parading her blue blocks around the giant sand pile.

For Rockwell, it all began with the purchase of an art desk for his children. “The day it arrived, I was excited to see how they were going to use it,” he recounts, “but when I came home, they were out in the hall in the cardboard box, with foam pellets all over.” Five years of research confirmed what his children had shown him in an instant: the playgrounds that provide kids with the most immersive and engaging experiences encourage them to make their own rules, create their own environments, take them apart and start all over again.

Busily constructing his own foam empire, Rockwell has recently wrapped up a seven-city European tour to promote Imagination Playground’s blue blocks, which store away in matching boxes when playtime ends; he is now selling the kit of “loose parts” online. While Rockwell is the playground’s current poster child, he is not the first to understand play as an integral part of mental simulation, and to build on it. In the 1930s, sculptor, artist and architect Isamu Noguchi, seeking “to bring sculpture into a more direct involvement with the common experience of living,” began what would expand into a decades-long exploration of playgrounds, by building interactive sculptures as well as integrated playscapes of sculpted earth. “For me,” Noguchi explained, “playgrounds are a way of creating the world.” Sadly, the vast majority of his designs went unrealized. He would later perceptively remark, “The things that do not happen are as valuable as the things that do happen, because the idea is there, and even if you won’t do it, somebody else will.”

Noguchi may finally be getting his grandstand moment. In June, The New York Times Magazine featured a list of “32 Innovations That Will Change Your Tomorrow.” More challenging playgrounds clocked in at number 17. The magazine noted two Norwegian psychologists, Leif Kennair and Ellen Sandseter, whose studies show that the restrictive safety standards that define most playgrounds have rendered them too safe for kids to truly test their limits. “Our fear of children being harmed by mostly harmless injuries,” they write, “may result in more fearful children and increased levels of psychopathology.”

Cultural critics might also heed what Martha Thorne, executive director of the Pritzker Architecture Prize, has said on the topic: “Just as museums were the commissions of choice for architects at the end of the twentieth century, the coveted assignment of the future could well be the urban playground.” With over half of the world’s children now growing up in urban environments, there is no better time to double our bets on inspiring public play spaces.

Elger Blitz, founder of the notable Dutch design agency Carve, would be the first to back Thorne’s hypothesis, and how Rockwell’s Imagination Playground facilitates the unexpected. “You need to give kids the freedom to discover how they want to use the play area in question,” affirms Blitz. “It’s nice when not everything spells out exactly how it should be used.” Having designed several of today’s most innovative playgrounds, Blitz – whose most recent, Van Beuningen Square in Amsterdam, seamlessly incorporates play areas and elements that appeal to children of various ages. Developed with Concrete Architectural Associates and Dijk&Co Landscape Architects, the project sits squarely at the top of the playground pyramid, with its integrated pavilions and wavy blue landscape. “Kids often find a single grand gesture much more interesting than a lot of separate activities,” he notes, revealing that the simple solution is often the most inspired.

The Danish-American firm MLRP beautifully illustrates a similar idea with its recent transformation of a graffiti-plagued structure in Copenhagen’s Interactive Playground Project. A flexible space used by kindergarten classes, Mirror House toys with perspective, reflection and transformation. MLRP converted both ends of its gabled structure into a giant funhouse mirror. Along the timber facade, large doors swing open to reveal convex and concave mirrors, further reflecting the surroundings, and brilliantly converting a dere-lict building into a beacon of delightful surprise.

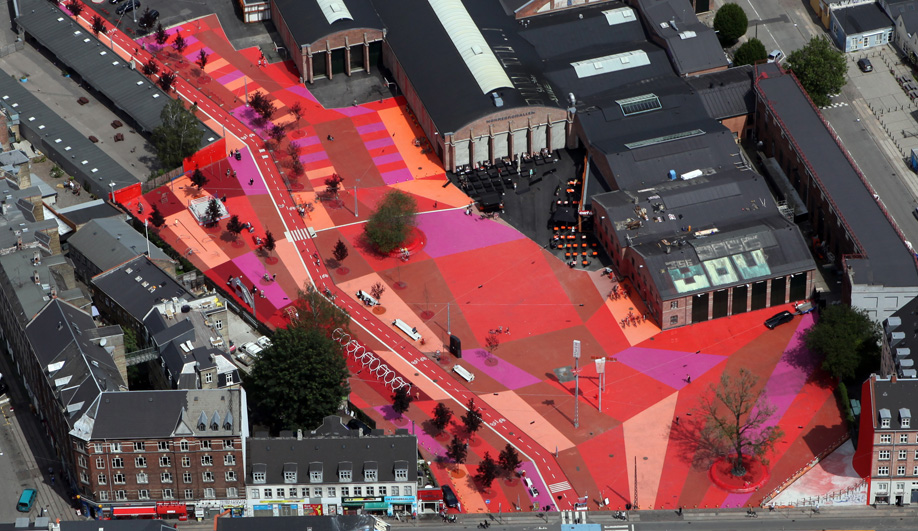

At Copenhagen’s Superkilen Red Square, a collaborative project by Bjarke Ingels Group, Topotek1 and Superflex, recreational activities are employed as a way to draw a diverse community together, bridging multicultural differences and infusing the urban framework with a sense of youthful liveliness. The open space is unified by its red epoxy resin-covered asphalt, and park furniture gathered from various parts of the world. It’s not always clear what some of the pieces are for, which opens up the possibilities for spontaneous invention and creative horsing around.

Such playgrounds as Red Square, which don’t prescribe to a set age group, can be impressively transformative for an entire community, not just youth. In Toronto, the recently opened Underpass Park, which extends beneath the Gardiner Expressway, is intended to remove some of the bleaker aspects of urban living, while creating a hub for the burgeoning neighbourhood now being built around it. Less permanent projects work in a similar way. With 21 Balançoires, the Montreal collective Daily Tous les Jours placed 21 music-al swings in the city’s downtown core. Each one triggered a different note when activated, prompting people to co-operate with one another to create their own harmonies.

The benefits of play extend to all ages. As a public design tool, it has the power to engage us with our surroundings by encouraging us to care more about our cities. “When enough people raise play to the status it deserves in our lives,” writes Dr. Stuart Brown, a pioneer in research on play, “we will find the world a better place.” Perhaps Noguchi’s dark horse will finally get his moment in the sun.