A former factory turned intentionally raw gallery, Toronto’s new Museum of Contemporary Art was crafted for the city it serves, not Instagram.

When Peter Clewes, principal of the Toronto firm architectsAlliance, was hired to turn an abandoned factory into an art gallery, he committed to using the lightest touch possible. Upon visiting the newly opened site, called the Museum of Contemporary Art Toronto, one might struggle to spot evidence of his and his firm’s work. “If you’re not even aware of what we did,” says Clewes, “that’s good news.”

It’s not as if Clewes did nothing. He had the existing terrazzo floors ground down, installed the necessary piping and ductwork and added both a new elevator shaft and a western entrance, which is topped with a sawtooth roof. His one regret? That he might have done less. “My only gripe is that I didn’t make the project as minimal as it could be,” he says. “I should have been even more discreet.”

Clewes’s re-design may be the furthest thing from bold, insomuch as it makes few efforts to transform the space. Yet it radiates confidence. It is the work of an architect who sees subtlety and transparency as the highest measures of success. Instead of showing off, Clewes let the original building – an idiosyncratic, century-old skyscraper known as the Tower Automotive Building – speak for itself. (His office worked in collaboration with ERA Architects, a firm with a heritage-conservation practice, which insisted that Clewes maintain the original facade, a demand with which he was all too happy to comply.)

The building is located in the Junction Triangle, a west-end industrial (and now, mostly, postindustrial) enclave that developers are touting as the next big thing. The structure was built from 1919 to 1920 by the Northern Aluminum Company, a maker of utensils, bottle caps and meter covers, and was eventually taken over by auto-parts manufacturer Tower Automotive, the last occupant before the plant was shuttered in 2006.

The construction of the tower consummated the rise of the Junction Triangle, a region that, like many in the city, seems to have appeared out of nowhere. The area was rural as recently as the 1870s but by the early 20th century had become a mess of stockyards, taverns, foundries and charcoal pools. The emergence of this west-end hub was part of a larger transformation: Toronto, formerly a port town centred on Lake Ontario, was becoming a rail metropolis comprised of multiple, diffuse neighbourhoods. (The name “Junction” refers to a nearby convergence of railway lines.)

For much of its life, the factory – 10 storeys of brick and concrete – was the tallest building in sight. It’s still the quirkiest. Unlike the Victorian post-and-beam warehouses of old Toronto, the Tower Automotive Building is, well, a tower. One wonders why the Northern Aluminum Company commissioned such an oddly vertical plant. Were they motivated by land-use costs? Or was the building’s engineer, C.A.P. Turner, an early practitioner of concrete-slab construction, unwilling to do anything else?

The most likely explanation is that the aluminum company was trying, in its awkward way, to make its mark on the neighbourhood. The exterior facade of the tower has its share of elegant detailing, from the belt course separating the ninth and 10th levels to the top-floor cornice accented with dentils.

Yet these pretensions are undercut by expedience. The mushroom columns running throughout the interiors are, by necessity, bulky, since they’re made of crude, minimally reinforced concrete. (Interestingly, they get progressively smaller on each floor.) And the punched windows, Clewes noticed, aren’t as big as they should be: They don’t quite reach the pilasters that flank them on either side. This design element made sense – in 1919, thanks to the advent of electricity, factory owners no longer needed expansive fenestration – yet it looks cheap all the same.

In short, the Tower Automotive Building is neither as simple as it could have been nor as gracious as it pretends to be. In this respect, it is of a piece with many earlier Toronto buildings: try-hard Victorian and Edwardian structures that are nonetheless often charming, even as they fail to imitate their more sophisticated counterparts in New York or London.

For Mary MacDonald, the senior manager in charge of heritage preservation in the city, the strangeness and coarseness of the tower accounts for much of its appeal. “When people think about heritage buildings, it is common for them to picture a pretty Victorian world, whether it’s a commercial street front or a house with gingerbread trim,” she says. “But heritage value is found in so many other different ways. I’m interested in making sure that, when it comes to conservation in the city, we remain broad-minded about what we consider to be valuable – and we move beyond the beauty contest.”

For conservationists, she says, the ideal tenants are the low-maintenance kind, who want to honour a building without eviscerating or sanitizing it. When, in 2015, the Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art (or MOCCA, as it was then known) was evicted from its bland gallery in the trendy West Queen West neighbourhood, the board seized the chance to move somewhere better. The Tower Automotive Building was empty, having been purchased by developer Castlepoint Numa, whose management envisioned a mix of cultural and commercial uses for the site. MOCA Toronto now occupies the bottom five floors.

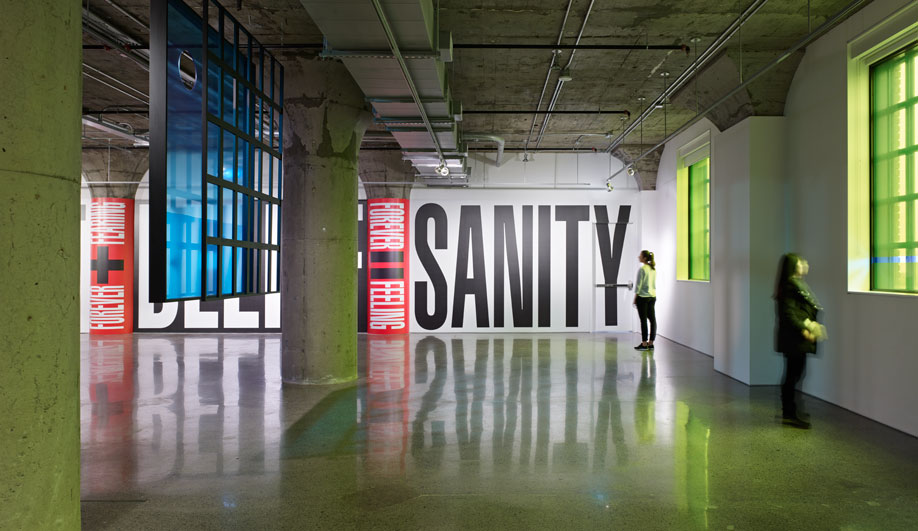

A few days after the gallery opened in September 2018, I toured it with Heidi Reitmaier, the executive director and CEO. The main interior feature is the temporary-exhibition space on the second and third floors, which will be devoted to group and solo shows. The inaugural exhibition, Believe, leaned heavily toward mixed media, new media and conceptual works from Canadian and international artists, only one of whom, Barbara Kruger, is rock-star famous. The interiors were notable for their ruggedness: filtered light, cracked terrazzo and those mushroom columns, like chunky stalactites, that break up the cavernous space.

MOCA Toronto’s other defining feature is its sense of civic purpose. The fourth and fifth floors include studios rented at below-market rates as well as a project space where emerging and mid-career artists will be commissioned for site-specific work. The ground floor, which Reitmaier calls the “front porch,” will always have a participatory art piece and will never cost money to enter. Currently, the space features the work of Greek artist and architect Andreas Angelidakis, who installed 74 high-density foam blocks – an invitation to patrons to build their own forts.

The new MOCA doesn’t have the wow factor you’ll find in other repurposed art institutions, such as Herzog & de Meuron’s recent Tate Modern extension in London or the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa in Cape Town, a grain silo transformed into a kind of steam-punk apiary by eccentric British designer Thomas Heatherwick. But MOCA Toronto doesn’t need wow. The city is desperate not for bold urban follies but for places to display art, particularly the kind that is too new for legacy institutions and too unconventional for commercial galleries. The project succeeds because it is both sensitive to the region’s history and responsive to its needs. It is a museum for Toronto, not Instagram.

When Reitmaier took over as CEO in 2018, the design for the retrofit was almost complete. The few changes she made were aimed at enhancing the sense of amicability. She removed partitions on the ground floor and redrew the eastern entrance. “The door was a single-person entrance and I made it a double, so visitors could come in side by side,” she says. Reitmaier wants the site, despite its imposing facade and rough industrial ambience, to be known as the friendly neighbourhood gallery. Plus, she adds, “most of us go to museums in twos.”

This story was taken from the January/February 2019 issue of Azure. Buy a copy of the issue here, or subscribe here.

When Peter Clewes, principal of the Toronto firm architectsAlliance, was hired to turn an abandoned factory into an art gallery, he committed to using the lightest touch possible. Upon visiting the newly opened site, called the Museum of Contemporary Art Toronto, one might struggle to spot evidence of his and his firm’s work. “If you’re not even aware of what we did,” says Clewes, “that’s good news.”

It’s not as if Clewes did nothing. He had the existing terrazzo floors ground down, installed the necessary piping and ductwork and added both a new elevator shaft and a western entrance, which is topped with a sawtooth roof. His one regret? That he might have done less. “My only gripe is that I didn’t make the project as minimal as it could be,” he says. “I should have been even more discreet.”

Clewes’s re-design may be the furthest thing from bold, insomuch as it makes few efforts to transform the space. Yet it radiates confidence. It is the work of an architect who sees subtlety and transparency as the highest measures of success. Instead of showing off, Clewes let the original building – an idiosyncratic, century-old skyscraper known as the Tower Automotive Building – speak for itself. (His office worked in collaboration with ERA Architects, a firm with a heritage-conservation practice, which insisted that Clewes maintain the original facade, a demand with which he was all too happy to comply.)

The building is located in the Junction Triangle, a west-end industrial (and now, mostly, postindustrial) enclave that developers are touting as the next big thing. The structure was built from 1919 to 1920 by the Northern Aluminum Company, a maker of utensils, bottle caps and meter covers, and was eventually taken over by auto-parts manufacturer Tower Automotive, the last occupant before the plant was shuttered in 2006.

The construction of the tower consummated the rise of the Junction Triangle, a region that, like many in the city, seems to have appeared out of nowhere. The area was rural as recently as the 1870s but by the early 20th century had become a mess of stockyards, taverns, foundries and charcoal pools. The emergence of this west-end hub was part of a larger transformation: Toronto, formerly a port town centred on Lake Ontario, was becoming a rail metropolis comprised of multiple, diffuse neighbourhoods. (The name “Junction” refers to a nearby convergence of railway lines.)

For much of its life, the factory – 10 storeys of brick and concrete – was the tallest building in sight. It’s still the quirkiest. Unlike the Victorian post-and-beam warehouses of old Toronto, the Tower Automotive Building is, well, a tower. One wonders why the Northern Aluminum Company commissioned such an oddly vertical plant. Were they motivated by land-use costs? Or was the building’s engineer, C.A.P. Turner, an early practitioner of concrete-slab construction, unwilling to do anything else?

The most likely explanation is that the aluminum company was trying, in its awkward way, to make its mark on the neighbourhood. The exterior facade of the tower has its share of elegant detailing, from the belt course separating the ninth and 10th levels to the top-floor cornice accented with dentils.

Yet these pretensions are undercut by expedience. The mushroom columns running throughout the interiors are, by necessity, bulky, since they’re made of crude, minimally reinforced concrete. (Interestingly, they get progressively smaller on each floor.) And the punched windows, Clewes noticed, aren’t as big as they should be: They don’t quite reach the pilasters that flank them on either side. This design element made sense – in 1919, thanks to the advent of electricity, factory owners no longer needed expansive fenestration – yet it looks cheap all the same.

In short, the Tower Automotive Building is neither as simple as it could have been nor as gracious as it pretends to be. In this respect, it is of a piece with many earlier Toronto buildings: try-hard Victorian and Edwardian structures that are nonetheless often charming, even as they fail to imitate their more sophisticated counterparts in New York or London.

For Mary MacDonald, the senior manager in charge of heritage preservation in the city, the strangeness and coarseness of the tower accounts for much of its appeal. “When people think about heritage buildings, it is common for them to picture a pretty Victorian world, whether it’s a commercial street front or a house with gingerbread trim,” she says. “But heritage value is found in so many other different ways. I’m interested in making sure that, when it comes to conservation in the city, we remain broad-minded about what we consider to be valuable – and we move beyond the beauty contest.”

For conservationists, she says, the ideal tenants are the low-maintenance kind, who want to honour a building without eviscerating or sanitizing it. When, in 2015, the Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art (or MOCCA, as it was then known) was evicted from its bland gallery in the trendy West Queen West neighbourhood, the board seized the chance to move somewhere better. The Tower Automotive Building was empty, having been purchased by developer Castlepoint Numa, whose management envisioned a mix of cultural and commercial uses for the site. MOCA Toronto now occupies the bottom five floors.

A few days after the gallery opened in September 2018, I toured it with Heidi Reitmaier, the executive director and CEO. The main interior feature is the temporary-exhibition space on the second and third floors, which will be devoted to group and solo shows. The inaugural exhibition, Believe, leaned heavily toward mixed media, new media and conceptual works from Canadian and international artists, only one of whom, Barbara Kruger, is rock-star famous. The interiors were notable for their ruggedness: filtered light, cracked terrazzo and those mushroom columns, like chunky stalactites, that break up the cavernous space.

MOCA Toronto’s other defining feature is its sense of civic purpose. The fourth and fifth floors include studios rented at below-market rates as well as a project space where emerging and mid-career artists will be commissioned for site-specific work. The ground floor, which Reitmaier calls the “front porch,” will always have a participatory art piece and will never cost money to enter. Currently, the space features the work of Greek artist and architect Andreas Angelidakis, who installed 74 high-density foam blocks – an invitation to patrons to build their own forts.

The new MOCA doesn’t have the wow factor you’ll find in other repurposed art institutions, such as Herzog & de Meuron’s recent Tate Modern extension in London or the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa in Cape Town, a grain silo transformed into a kind of steam-punk apiary by eccentric British designer Thomas Heatherwick. But MOCA Toronto doesn’t need wow. The city is desperate not for bold urban follies but for places to display art, particularly the kind that is too new for legacy institutions and too unconventional for commercial galleries. The project succeeds because it is both sensitive to the region’s history and responsive to its needs. It is a museum for Toronto, not Instagram.

When Reitmaier took over as CEO in 2018, the design for the retrofit was almost complete. The few changes she made were aimed at enhancing the sense of amicability. She removed partitions on the ground floor and redrew the eastern entrance. “The door was a single-person entrance and I made it a double, so visitors could come in side by side,” she says. Reitmaier wants the site, despite its imposing facade and rough industrial ambience, to be known as the friendly neighbourhood gallery. Plus, she adds, “most of us go to museums in twos.”

This story was taken from the January/February 2019 issue of Azure. Buy a copy of the issue here, or subscribe here.

The construction of the tower consummated the rise of the Junction Triangle, a region that, like many in the city, seems to have appeared out of nowhere. The area was rural as recently as the 1870s but by the early 20th century had become a mess of stockyards, taverns, foundries and charcoal pools. The emergence of this west-end hub was part of a larger transformation: Toronto, formerly a port town centred on Lake Ontario, was becoming a rail metropolis comprised of multiple, diffuse neighbourhoods. (The name “Junction” refers to a nearby convergence of railway lines.)

For much of its life, the factory – 10 storeys of brick and concrete – was the tallest building in sight. It’s still the quirkiest. Unlike the Victorian post-and-beam warehouses of old Toronto, the Tower Automotive Building is, well, a tower. One wonders why the Northern Aluminum Company commissioned such an oddly vertical plant. Were they motivated by land-use costs? Or was the building’s engineer, C.A.P. Turner, an early practitioner of concrete-slab construction, unwilling to do anything else?

The most likely explanation is that the aluminum company was trying, in its awkward way, to make its mark on the neighbourhood. The exterior facade of the tower has its share of elegant detailing, from the belt course separating the ninth and 10th levels to the top-floor cornice accented with dentils.

Yet these pretensions are undercut by expedience. The mushroom columns running throughout the interiors are, by necessity, bulky, since they’re made of crude, minimally reinforced concrete. (Interestingly, they get progressively smaller on each floor.) And the punched windows, Clewes noticed, aren’t as big as they should be: They don’t quite reach the pilasters that flank them on either side. This design element made sense – in 1919, thanks to the advent of electricity, factory owners no longer needed expansive fenestration – yet it looks cheap all the same.

In short, the Tower Automotive Building is neither as simple as it could have been nor as gracious as it pretends to be. In this respect, it is of a piece with many earlier Toronto buildings: try-hard Victorian and Edwardian structures that are nonetheless often charming, even as they fail to imitate their more sophisticated counterparts in New York or London.

For Mary MacDonald, the senior manager in charge of heritage preservation in the city, the strangeness and coarseness of the tower accounts for much of its appeal. “When people think about heritage buildings, it is common for them to picture a pretty Victorian world, whether it’s a commercial street front or a house with gingerbread trim,” she says. “But heritage value is found in so many other different ways. I’m interested in making sure that, when it comes to conservation in the city, we remain broad-minded about what we consider to be valuable – and we move beyond the beauty contest.”

For conservationists, she says, the ideal tenants are the low-maintenance kind, who want to honour a building without eviscerating or sanitizing it. When, in 2015, the Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art (or MOCCA, as it was then known) was evicted from its bland gallery in the trendy West Queen West neighbourhood, the board seized the chance to move somewhere better. The Tower Automotive Building was empty, having been purchased by developer Castlepoint Numa, whose management envisioned a mix of cultural and commercial uses for the site. MOCA Toronto now occupies the bottom five floors.

A few days after the gallery opened in September 2018, I toured it with Heidi Reitmaier, the executive director and CEO. The main interior feature is the temporary-exhibition space on the second and third floors, which will be devoted to group and solo shows. The inaugural exhibition, Believe, leaned heavily toward mixed media, new media and conceptual works from Canadian and international artists, only one of whom, Barbara Kruger, is rock-star famous. The interiors were notable for their ruggedness: filtered light, cracked terrazzo and those mushroom columns, like chunky stalactites, that break up the cavernous space.

MOCA Toronto’s other defining feature is its sense of civic purpose. The fourth and fifth floors include studios rented at below-market rates as well as a project space where emerging and mid-career artists will be commissioned for site-specific work. The ground floor, which Reitmaier calls the “front porch,” will always have a participatory art piece and will never cost money to enter. Currently, the space features the work of Greek artist and architect Andreas Angelidakis, who installed 74 high-density foam blocks – an invitation to patrons to build their own forts.

The new MOCA doesn’t have the wow factor you’ll find in other repurposed art institutions, such as Herzog & de Meuron’s recent Tate Modern extension in London or the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa in Cape Town, a grain silo transformed into a kind of steam-punk apiary by eccentric British designer Thomas Heatherwick. But MOCA Toronto doesn’t need wow. The city is desperate not for bold urban follies but for places to display art, particularly the kind that is too new for legacy institutions and too unconventional for commercial galleries. The project succeeds because it is both sensitive to the region’s history and responsive to its needs. It is a museum for Toronto, not Instagram.

When Reitmaier took over as CEO in 2018, the design for the retrofit was almost complete. The few changes she made were aimed at enhancing the sense of amicability. She removed partitions on the ground floor and redrew the eastern entrance. “The door was a single-person entrance and I made it a double, so visitors could come in side by side,” she says. Reitmaier wants the site, despite its imposing facade and rough industrial ambience, to be known as the friendly neighbourhood gallery. Plus, she adds, “most of us go to museums in twos.”

This story was taken from the January/February 2019 issue of Azure. Buy a copy of the issue here, or subscribe here.

When Peter Clewes, principal of the Toronto firm architectsAlliance, was hired to turn an abandoned factory into an art gallery, he committed to using the lightest touch possible. Upon visiting the newly opened site, called the Museum of Contemporary Art Toronto, one might struggle to spot evidence of his and his firm’s work. “If you’re not even aware of what we did,” says Clewes, “that’s good news.”

It’s not as if Clewes did nothing. He had the existing terrazzo floors ground down, installed the necessary piping and ductwork and added both a new elevator shaft and a western entrance, which is topped with a sawtooth roof. His one regret? That he might have done less. “My only gripe is that I didn’t make the project as minimal as it could be,” he says. “I should have been even more discreet.”

Clewes’s re-design may be the furthest thing from bold, insomuch as it makes few efforts to transform the space. Yet it radiates confidence. It is the work of an architect who sees subtlety and transparency as the highest measures of success. Instead of showing off, Clewes let the original building – an idiosyncratic, century-old skyscraper known as the Tower Automotive Building – speak for itself. (His office worked in collaboration with ERA Architects, a firm with a heritage-conservation practice, which insisted that Clewes maintain the original facade, a demand with which he was all too happy to comply.)

The building is located in the Junction Triangle, a west-end industrial (and now, mostly, postindustrial) enclave that developers are touting as the next big thing. The structure was built from 1919 to 1920 by the Northern Aluminum Company, a maker of utensils, bottle caps and meter covers, and was eventually taken over by auto-parts manufacturer Tower Automotive, the last occupant before the plant was shuttered in 2006.

The construction of the tower consummated the rise of the Junction Triangle, a region that, like many in the city, seems to have appeared out of nowhere. The area was rural as recently as the 1870s but by the early 20th century had become a mess of stockyards, taverns, foundries and charcoal pools. The emergence of this west-end hub was part of a larger transformation: Toronto, formerly a port town centred on Lake Ontario, was becoming a rail metropolis comprised of multiple, diffuse neighbourhoods. (The name “Junction” refers to a nearby convergence of railway lines.)

For much of its life, the factory – 10 storeys of brick and concrete – was the tallest building in sight. It’s still the quirkiest. Unlike the Victorian post-and-beam warehouses of old Toronto, the Tower Automotive Building is, well, a tower. One wonders why the Northern Aluminum Company commissioned such an oddly vertical plant. Were they motivated by land-use costs? Or was the building’s engineer, C.A.P. Turner, an early practitioner of concrete-slab construction, unwilling to do anything else?

The most likely explanation is that the aluminum company was trying, in its awkward way, to make its mark on the neighbourhood. The exterior facade of the tower has its share of elegant detailing, from the belt course separating the ninth and 10th levels to the top-floor cornice accented with dentils.

Yet these pretensions are undercut by expedience. The mushroom columns running throughout the interiors are, by necessity, bulky, since they’re made of crude, minimally reinforced concrete. (Interestingly, they get progressively smaller on each floor.) And the punched windows, Clewes noticed, aren’t as big as they should be: They don’t quite reach the pilasters that flank them on either side. This design element made sense – in 1919, thanks to the advent of electricity, factory owners no longer needed expansive fenestration – yet it looks cheap all the same.

In short, the Tower Automotive Building is neither as simple as it could have been nor as gracious as it pretends to be. In this respect, it is of a piece with many earlier Toronto buildings: try-hard Victorian and Edwardian structures that are nonetheless often charming, even as they fail to imitate their more sophisticated counterparts in New York or London.

For Mary MacDonald, the senior manager in charge of heritage preservation in the city, the strangeness and coarseness of the tower accounts for much of its appeal. “When people think about heritage buildings, it is common for them to picture a pretty Victorian world, whether it’s a commercial street front or a house with gingerbread trim,” she says. “But heritage value is found in so many other different ways. I’m interested in making sure that, when it comes to conservation in the city, we remain broad-minded about what we consider to be valuable – and we move beyond the beauty contest.”

For conservationists, she says, the ideal tenants are the low-maintenance kind, who want to honour a building without eviscerating or sanitizing it. When, in 2015, the Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art (or MOCCA, as it was then known) was evicted from its bland gallery in the trendy West Queen West neighbourhood, the board seized the chance to move somewhere better. The Tower Automotive Building was empty, having been purchased by developer Castlepoint Numa, whose management envisioned a mix of cultural and commercial uses for the site. MOCA Toronto now occupies the bottom five floors.

A few days after the gallery opened in September 2018, I toured it with Heidi Reitmaier, the executive director and CEO. The main interior feature is the temporary-exhibition space on the second and third floors, which will be devoted to group and solo shows. The inaugural exhibition, Believe, leaned heavily toward mixed media, new media and conceptual works from Canadian and international artists, only one of whom, Barbara Kruger, is rock-star famous. The interiors were notable for their ruggedness: filtered light, cracked terrazzo and those mushroom columns, like chunky stalactites, that break up the cavernous space.

MOCA Toronto’s other defining feature is its sense of civic purpose. The fourth and fifth floors include studios rented at below-market rates as well as a project space where emerging and mid-career artists will be commissioned for site-specific work. The ground floor, which Reitmaier calls the “front porch,” will always have a participatory art piece and will never cost money to enter. Currently, the space features the work of Greek artist and architect Andreas Angelidakis, who installed 74 high-density foam blocks – an invitation to patrons to build their own forts.

The new MOCA doesn’t have the wow factor you’ll find in other repurposed art institutions, such as Herzog & de Meuron’s recent Tate Modern extension in London or the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa in Cape Town, a grain silo transformed into a kind of steam-punk apiary by eccentric British designer Thomas Heatherwick. But MOCA Toronto doesn’t need wow. The city is desperate not for bold urban follies but for places to display art, particularly the kind that is too new for legacy institutions and too unconventional for commercial galleries. The project succeeds because it is both sensitive to the region’s history and responsive to its needs. It is a museum for Toronto, not Instagram.

When Reitmaier took over as CEO in 2018, the design for the retrofit was almost complete. The few changes she made were aimed at enhancing the sense of amicability. She removed partitions on the ground floor and redrew the eastern entrance. “The door was a single-person entrance and I made it a double, so visitors could come in side by side,” she says. Reitmaier wants the site, despite its imposing facade and rough industrial ambience, to be known as the friendly neighbourhood gallery. Plus, she adds, “most of us go to museums in twos.”

This story was taken from the January/February 2019 issue of Azure. Buy a copy of the issue here, or subscribe here.

The construction of the tower consummated the rise of the Junction Triangle, a region that, like many in the city, seems to have appeared out of nowhere. The area was rural as recently as the 1870s but by the early 20th century had become a mess of stockyards, taverns, foundries and charcoal pools. The emergence of this west-end hub was part of a larger transformation: Toronto, formerly a port town centred on Lake Ontario, was becoming a rail metropolis comprised of multiple, diffuse neighbourhoods. (The name “Junction” refers to a nearby convergence of railway lines.)

For much of its life, the factory – 10 storeys of brick and concrete – was the tallest building in sight. It’s still the quirkiest. Unlike the Victorian post-and-beam warehouses of old Toronto, the Tower Automotive Building is, well, a tower. One wonders why the Northern Aluminum Company commissioned such an oddly vertical plant. Were they motivated by land-use costs? Or was the building’s engineer, C.A.P. Turner, an early practitioner of concrete-slab construction, unwilling to do anything else?

The most likely explanation is that the aluminum company was trying, in its awkward way, to make its mark on the neighbourhood. The exterior facade of the tower has its share of elegant detailing, from the belt course separating the ninth and 10th levels to the top-floor cornice accented with dentils.

Yet these pretensions are undercut by expedience. The mushroom columns running throughout the interiors are, by necessity, bulky, since they’re made of crude, minimally reinforced concrete. (Interestingly, they get progressively smaller on each floor.) And the punched windows, Clewes noticed, aren’t as big as they should be: They don’t quite reach the pilasters that flank them on either side. This design element made sense – in 1919, thanks to the advent of electricity, factory owners no longer needed expansive fenestration – yet it looks cheap all the same.

In short, the Tower Automotive Building is neither as simple as it could have been nor as gracious as it pretends to be. In this respect, it is of a piece with many earlier Toronto buildings: try-hard Victorian and Edwardian structures that are nonetheless often charming, even as they fail to imitate their more sophisticated counterparts in New York or London.

For Mary MacDonald, the senior manager in charge of heritage preservation in the city, the strangeness and coarseness of the tower accounts for much of its appeal. “When people think about heritage buildings, it is common for them to picture a pretty Victorian world, whether it’s a commercial street front or a house with gingerbread trim,” she says. “But heritage value is found in so many other different ways. I’m interested in making sure that, when it comes to conservation in the city, we remain broad-minded about what we consider to be valuable – and we move beyond the beauty contest.”

For conservationists, she says, the ideal tenants are the low-maintenance kind, who want to honour a building without eviscerating or sanitizing it. When, in 2015, the Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art (or MOCCA, as it was then known) was evicted from its bland gallery in the trendy West Queen West neighbourhood, the board seized the chance to move somewhere better. The Tower Automotive Building was empty, having been purchased by developer Castlepoint Numa, whose management envisioned a mix of cultural and commercial uses for the site. MOCA Toronto now occupies the bottom five floors.

A few days after the gallery opened in September 2018, I toured it with Heidi Reitmaier, the executive director and CEO. The main interior feature is the temporary-exhibition space on the second and third floors, which will be devoted to group and solo shows. The inaugural exhibition, Believe, leaned heavily toward mixed media, new media and conceptual works from Canadian and international artists, only one of whom, Barbara Kruger, is rock-star famous. The interiors were notable for their ruggedness: filtered light, cracked terrazzo and those mushroom columns, like chunky stalactites, that break up the cavernous space.

MOCA Toronto’s other defining feature is its sense of civic purpose. The fourth and fifth floors include studios rented at below-market rates as well as a project space where emerging and mid-career artists will be commissioned for site-specific work. The ground floor, which Reitmaier calls the “front porch,” will always have a participatory art piece and will never cost money to enter. Currently, the space features the work of Greek artist and architect Andreas Angelidakis, who installed 74 high-density foam blocks – an invitation to patrons to build their own forts.

The new MOCA doesn’t have the wow factor you’ll find in other repurposed art institutions, such as Herzog & de Meuron’s recent Tate Modern extension in London or the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa in Cape Town, a grain silo transformed into a kind of steam-punk apiary by eccentric British designer Thomas Heatherwick. But MOCA Toronto doesn’t need wow. The city is desperate not for bold urban follies but for places to display art, particularly the kind that is too new for legacy institutions and too unconventional for commercial galleries. The project succeeds because it is both sensitive to the region’s history and responsive to its needs. It is a museum for Toronto, not Instagram.

When Reitmaier took over as CEO in 2018, the design for the retrofit was almost complete. The few changes she made were aimed at enhancing the sense of amicability. She removed partitions on the ground floor and redrew the eastern entrance. “The door was a single-person entrance and I made it a double, so visitors could come in side by side,” she says. Reitmaier wants the site, despite its imposing facade and rough industrial ambience, to be known as the friendly neighbourhood gallery. Plus, she adds, “most of us go to museums in twos.”

This story was taken from the January/February 2019 issue of Azure. Buy a copy of the issue here, or subscribe here.

The construction of the tower consummated the rise of the Junction Triangle, a region that, like many in the city, seems to have appeared out of nowhere. The area was rural as recently as the 1870s but by the early 20th century had become a mess of stockyards, taverns, foundries and charcoal pools. The emergence of this west-end hub was part of a larger transformation: Toronto, formerly a port town centred on Lake Ontario, was becoming a rail metropolis comprised of multiple, diffuse neighbourhoods. (The name “Junction” refers to a nearby convergence of railway lines.)

For much of its life, the factory – 10 storeys of brick and concrete – was the tallest building in sight. It’s still the quirkiest. Unlike the Victorian post-and-beam warehouses of old Toronto, the Tower Automotive Building is, well, a tower. One wonders why the Northern Aluminum Company commissioned such an oddly vertical plant. Were they motivated by land-use costs? Or was the building’s engineer, C.A.P. Turner, an early practitioner of concrete-slab construction, unwilling to do anything else?

The most likely explanation is that the aluminum company was trying, in its awkward way, to make its mark on the neighbourhood. The exterior facade of the tower has its share of elegant detailing, from the belt course separating the ninth and 10th levels to the top-floor cornice accented with dentils.

Yet these pretensions are undercut by expedience. The mushroom columns running throughout the interiors are, by necessity, bulky, since they’re made of crude, minimally reinforced concrete. (Interestingly, they get progressively smaller on each floor.) And the punched windows, Clewes noticed, aren’t as big as they should be: They don’t quite reach the pilasters that flank them on either side. This design element made sense – in 1919, thanks to the advent of electricity, factory owners no longer needed expansive fenestration – yet it looks cheap all the same.

In short, the Tower Automotive Building is neither as simple as it could have been nor as gracious as it pretends to be. In this respect, it is of a piece with many earlier Toronto buildings: try-hard Victorian and Edwardian structures that are nonetheless often charming, even as they fail to imitate their more sophisticated counterparts in New York or London.

For Mary MacDonald, the senior manager in charge of heritage preservation in the city, the strangeness and coarseness of the tower accounts for much of its appeal. “When people think about heritage buildings, it is common for them to picture a pretty Victorian world, whether it’s a commercial street front or a house with gingerbread trim,” she says. “But heritage value is found in so many other different ways. I’m interested in making sure that, when it comes to conservation in the city, we remain broad-minded about what we consider to be valuable – and we move beyond the beauty contest.”

For conservationists, she says, the ideal tenants are the low-maintenance kind, who want to honour a building without eviscerating or sanitizing it. When, in 2015, the Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art (or MOCCA, as it was then known) was evicted from its bland gallery in the trendy West Queen West neighbourhood, the board seized the chance to move somewhere better. The Tower Automotive Building was empty, having been purchased by developer Castlepoint Numa, whose management envisioned a mix of cultural and commercial uses for the site. MOCA Toronto now occupies the bottom five floors.

A few days after the gallery opened in September 2018, I toured it with Heidi Reitmaier, the executive director and CEO. The main interior feature is the temporary-exhibition space on the second and third floors, which will be devoted to group and solo shows. The inaugural exhibition, Believe, leaned heavily toward mixed media, new media and conceptual works from Canadian and international artists, only one of whom, Barbara Kruger, is rock-star famous. The interiors were notable for their ruggedness: filtered light, cracked terrazzo and those mushroom columns, like chunky stalactites, that break up the cavernous space.

MOCA Toronto’s other defining feature is its sense of civic purpose. The fourth and fifth floors include studios rented at below-market rates as well as a project space where emerging and mid-career artists will be commissioned for site-specific work. The ground floor, which Reitmaier calls the “front porch,” will always have a participatory art piece and will never cost money to enter. Currently, the space features the work of Greek artist and architect Andreas Angelidakis, who installed 74 high-density foam blocks – an invitation to patrons to build their own forts.

The new MOCA doesn’t have the wow factor you’ll find in other repurposed art institutions, such as Herzog & de Meuron’s recent Tate Modern extension in London or the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa in Cape Town, a grain silo transformed into a kind of steam-punk apiary by eccentric British designer Thomas Heatherwick. But MOCA Toronto doesn’t need wow. The city is desperate not for bold urban follies but for places to display art, particularly the kind that is too new for legacy institutions and too unconventional for commercial galleries. The project succeeds because it is both sensitive to the region’s history and responsive to its needs. It is a museum for Toronto, not Instagram.

When Reitmaier took over as CEO in 2018, the design for the retrofit was almost complete. The few changes she made were aimed at enhancing the sense of amicability. She removed partitions on the ground floor and redrew the eastern entrance. “The door was a single-person entrance and I made it a double, so visitors could come in side by side,” she says. Reitmaier wants the site, despite its imposing facade and rough industrial ambience, to be known as the friendly neighbourhood gallery. Plus, she adds, “most of us go to museums in twos.”

This story was taken from the January/February 2019 issue of Azure. Buy a copy of the issue here, or subscribe here.