What used to be the boiler house and engine rooms for the Philips power plant in Eindhoven is now a creative hub for VanBerlo, one of Europe’s hottest design firms.

Not everyone gets to say they work in one of their city’s most iconic buildings. But leading Dutch product design and innovation agency VanBerlo recently achieved these bragging rights by relocating its headquarters to Eindhoven’s Philips power plant, a massive manufacturing complex that had been shuttered since 1992. Originally built in 1955 and spread across three vast industrial parks, the engine room and boiler house known as Strijp-T used to power all the Philips factories.

The building, which was converted and renovated by three practices – Rotterdam’s Atelier van Berlo, Eugelink Architectuur and De Bever Architecten of Eindhoven – is now known as the Innovation Powerhouse. The seductive idea is that the fuel being produced here is no longer coal, gas or oil but – you guessed it – innovation.

Turning an abandoned plant into a multi-tenant hub destined to attract the best start-ups was neither a swift nor painless undertaking. The site was officially designated as a municipal monument a year into the design process, and the project therefore required more permits along the way. What’s more, the interior was riddled with asbestos that took four years to remove. Even the machinery was covered in the stuff.

“There were these beautiful steel wheels, for example, but they were connected by rubber that had asbestos on it,” explains Janne van Berlo, principal and founder of Atelier van Berlo. Nothing could be salvaged, but since the architects were after a creative work environment, much of the equipment would have had to be moved out anyway.

In Eindhoven, there are already so many offices that are filled with old machinery. We wanted to do something different.”

The interior may have been stripped bare, but it hasn’t lost its character. The coffered concrete ceiling has been retained along with 5.2-metre-high windows typical of their era. The space features two original coal chutes, now converted, respectively, into a meeting room and a 30-square-metre auditorium. Located on the sixth floor, they are rented out by another tenant, a company that creates indoor LED-driven farming solutions. What’s more, the conversion project has reinstated a “missing” section of the power plant.

“If you look at the architect’s original drawings, the building was meant to be symmetrical,” explains van Berlo. “The building, which had been modified several times over the years, was never fully completed.” Two missing grids have now been added in the form of a vertical steel garden that doubles as an unusually attractive fire escape and houses a meeting room and a glass elevator. Doing something different was a deliberate choice. “Completing the building without showing what was old or what was new didn’t do the monument justice,” says van Berlo. “We wanted to show what could have been there and not pretend it had always been there.”

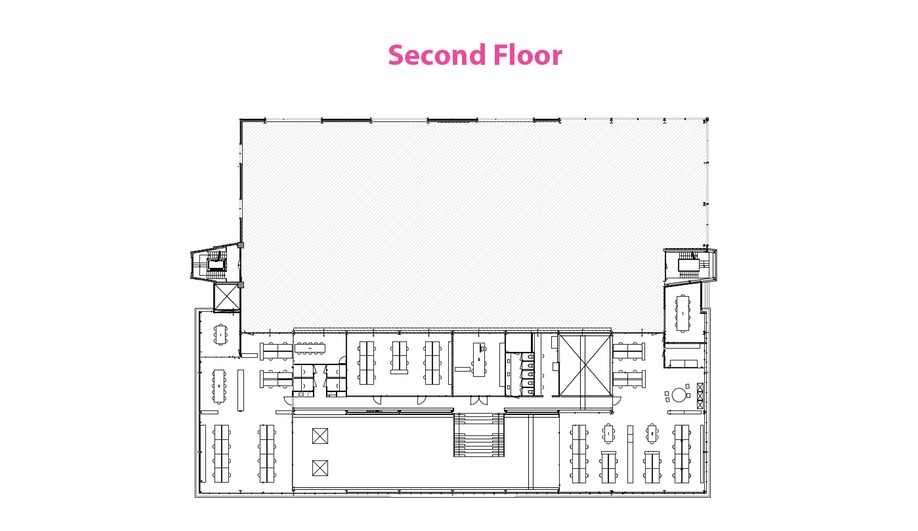

As anchor tenant and project initiator, VanBerlo wanted its offices to set the tone for the rest of the building. A new concrete storey the architects inserted was given a board-formed finish so that it had the same lived-in look as the original concrete. Varnished spruce was used on the floor, adding a warm atmosphere that impresses but doesn’t intimidate.

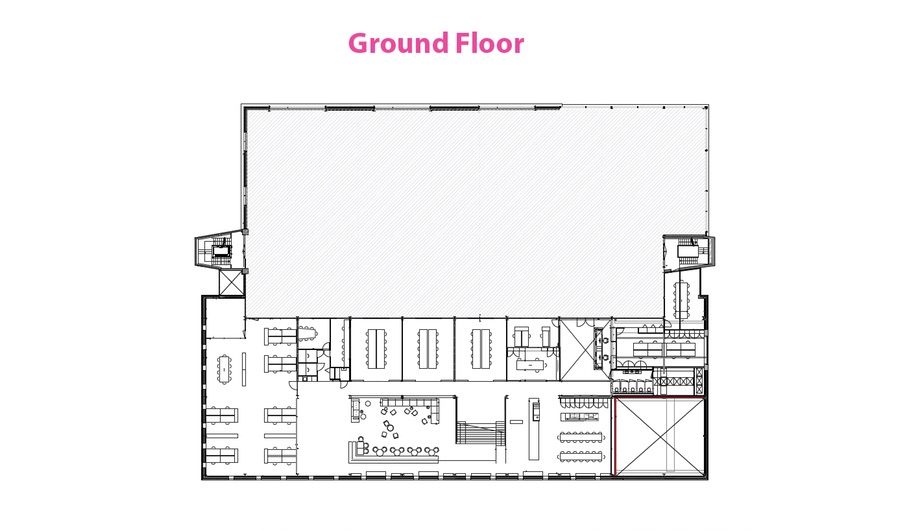

You enter the company’s 2,500-square-metre office via a reception area, where there is a desk made from battered H-profile construction beams. Above it, in a neat reference to the building’s origins, hang several old-school Philips fluorescent tubes that have been retrofitted with the company’s latest range of Wi-Fi-enabled, colour-changing LEDs. “It’s a nice mix of new technology and Philips history,” says van Berlo.

In keeping with the idea of a shared environment, the heart of the agency is a central communal space. In this double-height area are a sculptural walnut table and refectory-style tables as well as a Viroc coffee counter at one end. On the other side is a space with banquette and sofa seating, coffee tables and a showcase wall of spruce shelving units filled with projects the firm has been working on. This is where clients are welcomed and where informal meetings are held.

The lounge is raised one step up on a timber platform and connected to a wooden amphitheatre designed for group lectures. The massive room – lit by talented young Dutch designer Alex de Witte’s curvaceous Big Bubble lights hung as low as possible and populated with vibrant chairs and sofas by the likes of Vitra and Hay – feels a lot cozier than you’d expect. Even if you are sitting there alone and working, it feels intimate and protected.

The office’s design studios are located around this central space in a U-shape and separated by glass walls and oversized potted plants. “I am not a big fan of green walls because they’ve become a cliché,” says van Berlo. But putting in potted fiddle-leaf fig trees had the dual function of providing greenery and shielding the studios where confidential work takes place.

The building has its own coffee counter and kitchen, but, in true collaborative spirit, staff are encouraged to go down to the ground floor and eat in the restaurant, which is open to all the tenants and will eventually serve the public as well. In nice weather, tables and chairs spill outdoors. The ground floor also houses a glazed central “street” where staff and visitors can access the main staircase. “This space has multiple purposes,” explains van Berlo. “It gives structure to the building where all the tenant entrances are located, and it brings daylight in through a large skylight.” In lieu of a sterile lobby, this luminous space is where you can ask for directions or order a cup of barista-made, freshly ground coffee to enjoy on the terrace.

This story was taken from the June 2018 issue of Azure. Buy a copy of the issue here, or subscribe here.